"Access to archival materials stored in LASR may be limited at this time."

Search the Special Collections and Archives Portal

The Historic Landscape of Nevada: Development, Water, and the Natural Environment

- The Historic Landscape of Nevada: Development, Water, and the Natural Environment

- View All Images

- The Region

- Early Settlements & Ranches

- Irrigation

- Floods

- Las Vegas Land & Water Company

- Building a Water System

- Water Supply

- Water Quality

- Water Conservation & Waste

- The Politics of Water

- For Educators

- Educator Starting Points

- Getting to Know the Collection

- Primary Source Sets

- The Railroad & Water Rights

- Water to the New Subdivisions

- Municipal Ownership

- Water Shortage

- Water Level in Las Vegas

- Timeline - Educational materials

- About the Collection

- Digitizing the Collection

The persistence of the natural landscape and predominantly arid ecology of Nevada has created one of the greatest challenges facing the people of Nevada and the American West as we struggle to maintain our built environment. This project, The Historic Landscape of Nevada: Development, Water and the Natural Environment, documents the historic role of water resource management in Southern Nevada.

Since the nineteenth century, when the U.S. government first sent scientific expeditions to explore, map, and record the West, a voluminous record has been made of this landscape and the potential to exploit (and sometimes protect) it. Whether through irrigation, ranching, agriculture, dams, railroads, highways, towns, cities, or federal installations, the people of Nevada have challenged the environment in their attempt to make a desert flourish.

From the natural springs that attracted the earliest inhabitants and travelers, to the wells that supported early town development, to the massive federal reclamation projects that dammed the Colorado River to irrigate the California and Arizona deserts, water ruled. With the unparalleled, unexpected, and unplanned growth of the Las Vegas metropolitan area, the development of an urban and regional water system to support it has dominated natural resource planning and exploitation. The basic issues of water use—its quantity, quality, and allocation—still dominate policy and politics in Nevada and the Southwest, as Las Vegas seeks to tap surface and ground water sources in outlying counties and adjoining states, and as the original co-signers of the Colorado River Compact wrangle over the allocations from the dwindling water supplies of Lakes Mead and Powell.

Primary Source Sets for Educators

This collection contains several Primary Source sets designed to immediately connect educators with historical materials. These sets build on the wealth of digitized material in the Historic Landscape of Nevada and can be used to supplement teaching in a wide range of disciplines including: geoscience, math, political science, environmental science, history, and more! Use primary source sets to help reveal the deeper issues and most complex narratives of Nevada's historic landscape.

These sets of digitized images were selected and organized around key themes from the collection and provide educational focal points using five to ten historical documents that relate to a single theme (e.g., “Water Conservation”). Each set includes: a textual overview of the resources within the primary source set and a collection of suggestions for using the primary source set for learner enrichment. Each set also includes a timeline placing the material in historical context and visually representing the events in chronological order.

Choose one of the sets above or see our For Educators page to get started using the collection.

May 3, 1844-- After a day’s journey of 18 miles, in a northeasterly direction, we encamped in the midst of another very large basin, at a camping ground called las Vegas – a term which the Spaniards use to signify fertile or marshy plains . . . Two narrow streams of clear water, four or five feet deep, gush suddenly, with a quick current, from two singularly large springs; these, and other waters of the basin, pass out in a gap to the eastward. The taste of the water is good, but rather too warm to be agreeable . . . they, however, afforded a delightful bathing place.

John C. Fremont, Report of the Exploring Expedition to the Rocky Mountains, 1844

No grass, and difficult to get wood. Water brackish in the Virgin & could get no other . . . Tomorrow hope to reach the Muddy. Has been hot today & road for the most part through heavy sand. Tuesday Oct. 10th, 1848 Started this morning two hours before daylight and made a long march of 35 m. to the “Muddy” & over a very heavy road, without water or grass, by 12 o’clock! We made a delightful camp on a fine stream of water with good grass and found a large body of Indians—Piutes [sic]. From them we bought some corn and beans. And what a meal we made! The valley of “Muddy” is large & land fertile. The water is of the best and purest kind and some day, & that not too distant, this valley will teem with a large & healthy population.

Orvill C. Pratt, Diary, 1848.

A wide expanse of chaotic matter . . . consisting of huge hills, sandy deserts, cheerless, grassless plains, perpendicular rocks, loose barren clay, dissolving beds of sandstone and various other elements, lying in inconceivable confusion—in short, a country in ruins, dissolved by the peltings of the storms of ages, or turned inside out, up side down, by terrible convulsions in some former age. Eastward the view was bounded by vast tables of mountains one rising above another, and presenting a level summit at the horizon, as if the whole country had once occupied a certain level several thousand feet higher than its present and had been washed away, dissolved or sunk, leaving the monuments of its once exalted level smooth and fertile surface. Poor and worthless...

Parley P. Pratt, Report of the Southern Exploring Expedition presented to the legislative council of Deseret, 9 February 1850.

May terminated cold and cloudy although wind strong from the south. Fruit in great quantities and of unusual size. Grapes never better large bunches and well filled unusually large peach trees breaking down with peaches half grown – apricots in large quantities and plumbs -- in every respect an unusually fruitful year & unusually buggy. Everything grows from the very start without trouble, no coaxing is needed this year to make anything grow . . . July 7, Colorado River fell 4 feet no flood this year

O.D. Gass, Las Vegas Ranch Daybook, 1878

With the exception of the arable land of the Muddy, Santa Clara Creek, Pahranagat and Pah-rimp Valleys, and Las Vegas Springs, this section is typical of the desert in all its worst phases. . even the springs found at wide intervals throughout this large area are unreliable, often dry, and that many that were found active when visited are not necessarily permanent . . . the climate is that of the more southerly parts of the Great Basin; i.e. uniform and mild in winter; parching hot in summer . . . The permanent agricultural resources are slight, the grazing considerable, the timber limited, while there is a large field in which to discover and exploit the precious metals.

Captain George Wheeler, U.S. Geographical Surveys West of the 100th Meridian 1889

To describe this country and its sterility for one hundred miles, its gloomy barrenness, would subject the reader’s credulity to too high a strain. Not even the caw of a crow, or the bark of a wolf, was there to break the awful monotony. I could see something green on the tops of the distant mountains, a thousand feet above me, but here there was nothing but a continual stench of miasman, and hot strakes of poisonous air to breathe. Was this Hades, Sheole, or the place for the condign punishment of the wicked, or was it the grand sewer for the waste and filth of vast animation?

George W. Brimhall, The Workers of Utah, 1889

The Las Vegas Springs supported intermittent Native American inhabitation for millennia. The Paiutes often made seasonal encampments at the springs that usually lasted through the winter. The springs were a welcome stop on the Old Spanish Trail, as Spanish then American travelers traveled along the well-worn road.

The Mormons were the first whites to establish settlements in the region. In early 1855, Brigham Young decided to establish missions in present day Utah, Idaho, and Nevada to proselytize the Native Americans, teach them agriculture, and to open a safe road from Salt Lake to the Pacific. 30 missionaries were sent to Las Vegas, led by William Bringhurst. The missionaries experienced initial success, baptizing many, planting crops, and beginning construction on a fort. By 1857, internal tensions and conflict with the local Paiute had already threatened the mission when Brigham Young recalled the missionaries.

Mormon settlers later returned to the Muddy River Valley and settled St. Thomas, Overton, and Logandale, farming and ranching, and using the river to irrigate their fields.

When Hoover Dam began impounding water in February of 1935 forming Lake Mead, some of the earliest settlements disappeared under its waters, including Fort Callville, the head of navigation on the Colorado River; Bonelli’s Ferry at which a ferry operated until the 1920s; and St. Thomas, an agricultural settlement established by Mormon missionaries to grow cotton, which was important enough to warrant a railroad connection to the Salt Lake line in 1910. Also lost under Lake Mead was the Pueblo Grande of Nevada—known as the Lost City—an Anasazi site excavated in 1924, and reconstructed only to be washed away.

Inquiry:

What could justify growing cotton in Southern Nevada and transporting it via rail lines?

Ranching in Southern Nevada, like ranching in the other arid western states, was a hard outdoor life, eking out what would grow in the highly alkaline soil using what water was available and raising what livestock could survive on the scrub that grew near the water on the range.

The ranches in the Las Vegas Valley quite naturally grew around the natural springs: the Cottonwood Spring, the Las Vegas Spring, and the small springs that watered what became known as the Kyle Ranch. The land watered by the springs supported fruit orchards, grapes, and a variety of vegetables. Oats, barley, and wheat crops would alternate with beans, melons, squash, cabbage, beets, onions, and potatoes. The grass (in the field, or cut for hay) fed livestock, beef and dairy cattle, horses, and hogs and chickens. Livestock roamed freely on the grasslands, some corralled at night by ranch hands (often local native Americans). Manufactured goods and supplies had to be freighted in from California or Utah.

Inquiry:

Using only images from the collection, how would you characterize desert ranching using the Stewart Ranch as a case study?

The largest and most significant ranch was the Las Vegas Ranch, headquartered on the grounds of the old Mormon mission settlement on the Las Vegas Creek, with grasslands extending west along the creek to where the Las Vegas—or Big Springs—bubbled up from the ground. The ranch later became known as the Stewart ranch after its later owners Archibald Stewart and his wife Helen.

“ A vast area of the arid lands will ultimately be reclaimed and millions of men, women and children will find happy, rural homes in the sunny lands . . .”

John Wesley Powell, Report on the Lands of the Arid Region of the United States, 1878

“Emancipation”

Inquiry:

Would the tone of this poem change if written by: a.) Native Americans of the era or b.) Walter Bracken?

The Nation reaches its hand into the Desert

And lo! Private monopoly in water and in land is scourged

From that holiest of temples, -- the place where men

Labor and build their homes!The Nation reaches its hand into the Desert

The wasting floods stand back, the streams obey their

Master, and the stricken forests spring to life again

Upon the forsaken mountains!The Nation reaches its hand into the Desert

The barred doors of the sleeping empire are flung wide

Open to the eager and the willing, that they may

Enter in and claim their heritage!The Nation reaches its hand into the Desert

That which lay beyond the Grasp of the Individual yields

To the hand of Associated Man. Great is the

Achievement, -- greater the Prophesy!William E. Smythe, The Conquest of Arid America, 1899

“Clark buys ‘Oasis in the Desert: The famous Las Vegas Ranch'; tropical fruits, dates, figs etc. and the citrus fruits can be produced in a way to rival the most favored sections of southern California.”

Deseret News, October 18, 1902, reporting Senator Clark’s purchase of Helen Stewart’s ranch

Inquiry:

This prospectus invites investors to contribute funds to facilitate drilling artesian wells. Given only what was known about the Las Vegas Valley in 1905, would this appear to be a good investment choice?

“This is a home organization, we are all interested in the development of the Vegas valley and we solicit the aid, on an equal footing with us, of every person interested in the general prosperity of Las Vegas and the agricultural lands surrounding. We have many thousands of acres rich enough for farming, and level enough for irrigation. We have no known water supply. We believe that artesian water may be had in abundance. And by the following plan proposed we will acquire land and bore artesian wells, and each contributing will receive his share of the profits of our operations. We want all to subscribe to our stock . . . “

Vegas Artesian Water Syndicate, prospectus, incorporated November 1905

“Las Vegas, Nevada, where farming pays : the artesian belt of semi-tropic Nevada"

Las Vegas Chamber of Commerce, promotional brochure, 1912

Inquiry:

What motivation might the Las Vegas Chamber of Commerce of 1914 have had to encourage "the landless man" to relocate to the town?

SEMI-TROPICAL NEVADA: A Region of Fertile Soils and Flowing Wells. This Booklet is dedicated to the landless man who is seeking cheap lands which may be made valuable by small capital and his own labor.

Las Vegas Chamber of Commerce, promotional brochure, 1914

The great military and scientific surveys of the American West conducted by the U.S. government in the 19th century were directed ultimately toward the future settlement and exploitation of the West. Associated with the expeditions to survey and map a route for the transcontinental railroads were later geological and topographical studies to explore the feasibility of irrigation to support agriculture. Irrigating the desert by controlling and diverting entire river systems was a manifestation of American engineering destiny. The monument of this remains Hoover Dam, constructed—miles from the small town of Las Vegas—essentially to provide water and power for California and Arizona.

Ranching and agriculture in Southern Nevada depended upon irrigation, tapping and re-directing the natural springs and waterways into a patchwork of sluices and ditches. The region's rivers and streams, including the Las Vegas Creek, sustained localized agriculture, orchards, and even viniculture, and provided grass for cattle and stock. Farmers along the Colorado River used water wheels to raise irrigation water, and for a time the Moapa Valley exported rail cars of melons, asparagus, and other agricultural goods. Farmers still grow wheat and alfalfa in the Virgin River Valley with diverted river water, and farmers in the Amargosa Valley currently use center pivot irrigation for their crops.

Inquiry:

Contemporary aerial views of Southern Nevada would be unlikely to inspire those with agricultural interests. What differences as evidenced in aerial views from the late 19th and early 20th centuries suggested prime agricultural resources in Las Vegas and its surrounding valleys?

The perceived potential for irrigation to turn the Las Vegas Valley into a rich agricultural region became a theme for promoters and developers, as well as the city’s own Chamber of Commerce. But the Las Vegas Valley was not to become the new Southern California, as water was diverted increasingly to domestic and industrial use. The old Stewart Ranch would continue to operate as a dairy and cattle ranch under a variety of tenants, and the railroad would even contemplate creating a Model Farm there. But the Stewart Ranch was eventually swallowed up by the sprawling city. Ironically, the people of Las Vegas viewed Lake Mead not as a source of domestic water but for irrigation.

“Whatever man may do, nature will proceed uninterruptedly in its course . . ”

Captain George M. Wheeler, Geographical Surveys West of the One Hundredth Meridian, 1889

Inquiry:

Using resources in this collection and the book Cadillac Desert, do you feel Wheeler's comment is substantiated?

The problem with water in the desert is not always its scarcity, but sometimes the floods caused when it does rain. The hardpan, or caliche as it is known, is pervasive in the Las Vegas Valley. Caliche forms in both fine-grained and course-grained soil. Calcium carbonate accumulates under the surface in areas where evaporation exceeds precipitation, particularly in deserts. The calcium carbonate becomes cemented, creating a rock-like, impermeable layer which, when combined with other geological features, keeps much of the rainwater on the surface.

It does rain in Southern Nevada, but infrequently. When rain falls, the thin soil saturates quickly, funneling the runoff into gullies, washes, and streams. Flash flooding can turn a dry streambed into a raging torrent, destroying everything in its path including railroad tracks; the Salt Lake line was washed out on a number of occasions and at a number of locations. The lack of anchoring vegetation combined with large amounts of water can produce significant erosion, which human activity can exacerbate by disturbing soils and unintentionally redirecting floodwaters to places where there is no underlying hardpan.

Blocking the natural water courses of drainage in the valley by construction and urban development has worsened flooding, causing recurring and severe damage in the city of Las Vegas. Today, a regional flood control program utilizes a new system of retention basins, channels, and conduits through which runoff water is now more effectively channeled back into the natural water system.

Inquiry:

Varying flood channels existed in Las Vegas before and after the town’s beginnings. Where were these channels and what natural and manmade factors contributed to their direction and volume?

John Wittwer and flood control in the Moapa Valley

John Wittwer was the District Agricultural Extension Agent for Clark County who came to Southern Nevada in 1921 after having worked as an agent in his native Utah. The Cooperative Extension Service was established by the federal Smith-Lever Act of 1914 to stimulate farm production. It was a cooperative program between the U.S. Department of Agriculture and state agricultural colleges: in Nevada, the University of Nevada (Reno) Agricultural Extension Division. Each county was organized into county Farm Bureaus through which the extension programs were conducted. Activities included instruction and demonstrations for farmers, housewives, youth, ranchers, and stockmen. The Extension Service organized what later became 4-H Clubs throughout the state.

The Service was technically administered through the University's School of Agriculture and its Dean, but under its politically ambitious directors, it became a de facto independent agency. Wittwer served as county agent through 1951, and his primary concerns in Southern Nevada were soil improvement, flood control, water storage, drainage and irrigation, livestock development, and the establishment of the dairy industry. Wittmer also assisted in organizing and establishing the first CCC camp in Southern Nevada, in Kyle Canyon.

Inquiry:

How are the goals of the current Agricultural Extension Service similar to and different from those from 1930-1950?

Survey plans and specifications for flood control were turned over to the Engineering Division of the Forest Service, and CCC camps were used on flood control operations in Moapa, Virgin, Panaca, and Pahranagat Valleys. Wittwer’s reports contain detailed information about the activities of the Division and include many photographs; documenting various projects, including the flood control work in Southern Nevada during the winter of 1933 and 1934 by the Civilian Conservation Corps. Flood control, soil conservation, and irrigation were the critical factors for agriculture in Southern Nevada.

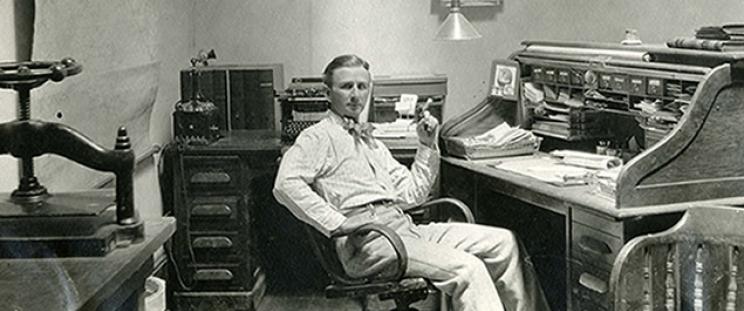

On July 13, 1950, Walter R. Bracken, former Vice President of the Las Vegas Land & Water Company and longtime local agent and representative of the Union Pacific Railroad, died in his home in Las Vegas. A lengthy obituary befitting a longstanding civic leader, local businessman, and “Pioneer of Las Vegas," appeared the next day in the Las Vegas Review Journal. “Whose history in Las Vegas,” according to the RJ, “spanned half a century and established him as the pioneer with the longest continuous residence in the community.” The article recounted this history, born in Ohio, educated in Washington, Pennsylvania (at Washington & Jefferson College, presumably), and trained as a civil engineer.

In 1901 he joined Carl Stradley as locating engineer for the Oregon Short Line railroad, which was surveying a route from Salt Lake to Los Angeles. “Traveling with a team and buckboard, he entered Las Vegas for the first time and found the Old Ranch, with its plentiful water supply as a logical division point for the railroad. Recommendations made by his party resulted in the purchase of the ranch from the late pioneer Mrs. Helen M. Stewart.”

The Senator William A. Clark of Montana, President of the San Pedro, Los Angeles & Salt Lake Railroad company “which undertook the project for establishing the missing railroad link from Utah to California, acted on the recommendation and purchased the ranch. Then, Senator Clark appointed Bracken to be representative of the railroad in Las Vegas, even before the construction began.”

The account then tells how Bracken “aided with the surveys of the proposed townsite,” arranged for lots to be set aside for churches and public buildings, and was present at the auction of the lots on May 15, 1905, “which marked the official start of Las Vegas.”

Walter Bracken was undoubtedly one of Las Vegas’ most prominent citizens. He was the first postmaster, a charter member of the Rotary Club, a member of the Elks Club, and the Chamber of Commerce. He served on the School Board and was a longtime Mason, charter member of Vegas Masonic Lodge number 32 in which he was given the signal honor of elevation to the thirty-third degree, the only thirty-three degree Mason in Southern Nevada. But perhaps more important than any of these Masonic degrees or civic functions, he was the local official for the Union Pacific Railroad and its subsidiary the Las Vegas Land & Water Company, which owned the land on which the town was built, and which controlled its water supply. And as representative of the railroad he was the face of the region’s largest company and employer. He was a true pioneer in Las Vegas; he and his wife had lived on the old Stewart ranch before moving into one of the first houses built of Fremont Street. So his history was, in some respects, the history of Las Vegas. And by 1950, when many of the original pioneers had passed away, “the pioneers” had acquired a certain iconic aura.

Bracken’s role in the coming of the railroad and creation of the city was more modest than later accounts would credit. He was a junior surveyor on one of the many railroad survey teams that passed through the Las Vegas Valley, and stopped at the well-known and much visited Stewart ranch and hostelry. His earliest position in Las Vegas was as the store clerk for his older brother who managed the Stewart ranch and store for the railroad until the Las Vegas townsite was laid out and the lots auctioned. After his brother’s return to Utah, Walter took up the lease on the ranch intending to make a living ranching. But Bracken soon wearied of the unprofitable ranch and like many others moved into the new town where there were more business opportunities. A family connection with the Stewarts who built the railroad—Senator William A. and his brother J.Ross—no doubt contributed to his being appointed the local agent for the new railroad and for the new Land & Water Company, which was to manage the railroad property and water system in Las Vegas.

The Salt Lake Route, as it was known, had always been controlled by the Union Pacific, despite Senator Clark’s being a titular partner, and his brother J. Ross being a 2nd Vice President, but after 1921 it was entirely the Union Pacific, one part of the nation’s largest rail system, with its headquarters in Omaha, and offices in Los Angeles. The railroad would be the biggest business, landowner and employer in Las Vegas for many years, controlling not just its water system but also tracts of industrial, commercial, and residential developments which it leased, sold, serviced, and maintained. Walter Bracken, as the representative of the railroad and through his own personal business associations and interests, was inextricably bound and engaged in all the business, political, and civic issues facing the growing city of Las Vegas. His correspondence document almost all aspects of life in the city from water shortages, tourism, and civic promotion, to strikes and labor unrest. And he proved a loyal and stalwart advocate and protector of the railroad and its interests in Las Vegas, for which he incurred, on occasion, the enmity of his neighbors.

When the railroad decided to establish a town on the Stewart ranch property in Las Vegas, the decision was made to incorporate a separate subsidiary company to sell the town lots, manage the railroads’ properties (including the ranch), and to build and manage the town’s water system. When the rail line was complete and the town site platted, the Las Vegas Land & Water Company was duly incorporated and the railroad’s property conveyed to it.

Inquiry:

Compare the desires of Union Pacific personnel with those of Walter Bracken. How did Bracken advocate for a stronger Southern Nevada and how might Southern Nevada be different today had more of the Union Pacific’s plans been implemented?

The Las Vegas Land & Water Company, despite it being, at least on the railroad’s account books, a separate company, was completely controlled by the railroad, and Walter Bracken, as Vice President of the Water Company, reported to the various railroad departments and offices and ultimately to the President of the Union Pacific System in Omaha. All decisions, no matter how petty (whether Bracken could buy a car and what kind, or whether he could have modern toilet facilities built in his house) were reviewed by a complex hierarchy of officials in Las Vegas, Los Angeles, and Omaha. Most departments maintained local offices: for example there was a railroad attorney in Las Vegas who reported to the Legal Department in Los Angeles, and the local engineering office in Las Vegas likewise reported to the chief engineer in Los Angeles. The Los Angeles office also handled all accounts and receipts both from the railroad and the Las Vegas Land & Water Company.

Decisions requiring corporate authorization were made in Omaha, whose officers closely monitored not only local railroad operations, but state and local political issues as well. Legal matters from contracts, leases, law suits, labor relations, and freight charges, to applications and permits for the appropriation of water and the digging of wells—anything which was regulated by either state of federal agencies—went through the Law Department. All construction, surveys, maintenance of buildings, track, or water pipes went through the engineering department.

The Las Vegas Artesian Basin lies within the Great Basin and Range geological region. The region is characterized by narrow faulted mountain ranges and flat, arid, valleys or basins. There are extensive maps in this collection showing this distinct geology. The mountains and the bedrock form a rough “V” shape that is filled in with various layers of rock and sediment that form the floor of the valley. The shape of the valley funnels water into an aquifer. Hydrostatic pressure brings this water to the surface mid-valley at the Las Vegas Springs. These springs produced the valley’s namesake. In Spanish, Las Vegas means “the meadows.”

When the route for the SP,LA&SL RR was laid out through the Las Vegas Valley and the right of way acquired by the railroad, the Stewart Ranch with its valuable springs and water rights were purchased by William A. Clark, president of the railroad, as a convenient division point for the railroad and watering stop for its locomotives and trains.

During the construction of the railroad a redwood stave pipe line was laid between the springs and the watering tower on the Las Vegas station grounds. Upon completion of the railroad line the railroad conveyed the ranch lands to its own newly incorporated subsidiary company, the Las Vegas Land & Water Company. After the town was platted and lots sold, the Las Vegas Land & Water Company laid its distribution system of water pipes through the new townsite. These pipes were also made of red wood staves. The Water Company’s system was connected at the edge of the station grounds to the railroad’s water main transmission line from the springs. The Water Company technically purchased it’s water from the railroad.

As the town grew, the supply of water from the springs alone proved inadequate and the water company drilled a series of wells, first in the vicinity of the original three springs, but later at a greater distance west of the springs. By 1954 when the Land & Water Company sold its entire water system to the Las Vegas Water District, it was operating 12 wells.

The water from the springs and wells passed through a settling basin to a reservoir. From the reservoir the water flowed by gravity to the town down an elevation of eighty-one feet over the two mile distance. As the water level of the aquifer which fed the springs was depleted and the supply from the springs declined, the water pressure in the city also declined. To augment water pressure to the city the LVL&W Company eventually installed pumps at its wells and a second main transmission line to the northern part of the city.

From 1905 to 1927 the Water Company only provided water to the original Clark’s Las Vegas townsite. In 1927 a line was extended north from the original transmission line to McWilliams’ original townsite on the west side of the railroad tracks. When developers created new subdivisions beyond the original townsite, water was provided through private water companies usually created for the purpose by the developer, which laid their own pipelines. These private water companies relied either on private wells or connected to the Water Company’s pipelines and purchased their water from the Water Company. As the subdivisions were built out and populated, these private water companies were unable to keep pace, were undercapitalized for construction and maintenance, and often went bankrupt or simply stopped providing service.

Inquiry:

How did procurement of small, privately owned water companies by the Las Vegas Land & Water Company change the fate of water in the Las Vegas Valley and should the Company have overtaken them? Retrospectively, did the procurement of these organization help or hurt the Las Vegas Land and Water Company in the short- or long-term?

The real estate speculation and housing boom associated with the construction of Hoover Dam saw an spread of new subdivisions. In 1928 the Las Vegas Land & Water Co. purchased the water system of the Hawkins Land and Water Company which had provided water to the Hawkins, Bucks, Fairview Subdivisions, and Pioneer Heights. In 1930 the LVL&W Company acquired the Parkview Mutual Water Company, and in 1934 the South Nevada Land & Development Company. In the 1940s the company extended its system to include most of the new subdivisions including the Federal Housing projects that had been built to accommodate the war construction boom. By the end of the war, the entire city—with very few exceptions—was provided with water by the Las Vegas Land & Water Company’s system.

The original pipelines in the city, including those laid by private companies, were mostly of wood stave until 1927 when the LVL&W Co. started replacing pipelines with cast iron pipes. In 1941 all the remaining wooden, as well as older wrought iron pipelines, were replaced by cast iron pipes. Nevada law did not permit customer water meters in cities with populations over 4,500, and the water rates were fixed by the terms of the water company’s franchise with the city of Las Vegas and by the Nevada Public Service Commission (originally at $1.00 a month per house on a 50X150 foot lot) regardless of amount of water used. The rate was increased to $2.00 a month in 1931.

Inquiry:

Since there were few profits from the Las Vegas Land & Water Company, what motivation did the railroad have for keeping it so long?

The Las Vegas Land & Water Company bore the cost of the maintenance and replacement of all its water facilities including pipelines. Considering that the Water Company also had to pay the railroad for all the water it used, its profits were usually negligible. The Union Pacific used the water company largely as a tax write-off.

“Most of the ground water used in the three valleys is obtained from wells and springs and is supplied by the gravel and sand lenses of the valley fill. In Las Vegas more than three-fourths of the wells draw water from aquifers ranging from 250 to 450 feet below land surface, designated as the Shallow Zone of aquifers.

Inquiry:

What is the significance of the depth of the aquifers and surrounding rock types from which water is drawn?

The only source of ground water for the three valleys is precipitation on the higher areas of the Spring and Sheep Mountains. However only a small part of the precipitation recharges the alluvial-fan and valley-fill materials that compose the ground-water reservoirs. The rest of the water from precipitation on the area is lost by evaporation and transpiration. The water that reaches the ground-water reservoirs is ultimately discharged through springs and wells and by evaporation and transpiration.”

Maxey and Jameson, Geology and Water Resources of Las Vegas, Pahrump, and Indian Spring Valleys, Clark and Nye Counties, Nevada, 1948

“I hear there is a chance to get a contract drilling water wells in Las Vegas, as water is very scarce in that part...”

George Wynecook, Bakersfield, CA to E.G. Tilton, chief engineer, SP,LA, & SL Railroad, letter, August 29, 1906

“Answering your letter of Aug. 29th in regard to drilling wells at Las Vegas, this company has no intention of drilling and wells there. As to whether or not anyone else is, I am unable to say. An abundance of water is received by gravity from springs in the neighborhood.”

Tilton to Wynecook, letter, August 31, 1906

“Our attention has been directed to the fact that the water supply at Las Vegas is becoming inadequate...”

Pacific Fruit Express Co. [owners of the Ice plant] to Walter Bracken, letter, November 11, 1922

“One of the most vital and pressing questions confronting the City of Las Vegas is the matter of an increase of water supply and the extension of the water mains to subdivisions which are very badly in need of water, (as some have none), therefore holding back the upbuilding of these subdivisions. Many are now complaining that they have not water enough for family use under the present water system in said subdivisions. The City Board would like to hear from the Las Vegas Land & Water Company, as to what steps it intends to take, if any, in regard to further supply of water . . . “

W.H. Dentner, Las Vegas Mayor pro Tem. to Bracken, letter, March 20, 1923

“I respectfully submit herewith an estimate which I believe will cover the rehabilitation of the eighteen hundred acre ranch at Las Vegas, Nevada, owned jointly by the Railroad Company and the Las Vegas Land and Water Company, and make it not only a productive, but demonstration ranch second to none in the west. In this case the dominant interest IS PROTECTION OF OUR WATER RIGHTS to conform to our Nevada State laws, and second…

Walter R. Bracken to E.E. Calvin, letter, March 9, 1926

“we have an abundance of water for the being, but the facilities for conducting the water to the Railroad and Townsite are inadequate . . . Next year if the town continues to grow as it has in the past, and the Boulder Canyon Dam Bill should be passed, it would possibly double our population . . .

Walter R. Bracken to Howard C. Mann, Chief Engineer UP System, letter, April 26, 1928

“While we are anxious to keep pace with genuine development, we have learned from experience that careful judgment must be exercised in considering requests for water main extensions. By this I mean we do not intend to extend water mains into vacant blocks on the outskirts of the city, thereby increasing the value of such lots at the expense of the Water Company. The result of such action on our part has been that the owner immediately increases the sale price of his lots to the point where it is prohibitive, thereby depriving the water company of potential customers . . Where there is a genuine development on outlying districts that would justify our extending our water mains therein at our own expense, appropriate requests for such investment will be submitted when we can justify a favorable return of earnings thereon.”

Walter Bracken to Frank Strong, Vice-President of LVL&W Co. in Los Angeles, letter, April 11, 1940

“There will be a tremendous development in the immediate area surrounding Las Vegas as a result of expanding national defense. There is no place in America which will develop and develop as fast as Las Vegas in the near future. Whether this development goes as far as is now indicated it will, depends largely on an adequate water supply . . . We can develop enough water from underground sources for ordinary use, but for big operations such as are now planned for Las Vegas there is only one source that is sufficient – Lake Mead.”

W.M. Jeffers, President of UP System, address to the Las Vegas Rotary Club, June 18, 1941

Inquiry:

There appears to be an ongoing conflict within the water company—a need for more water and a need to extend water mains to outlying areas due to increased population. What methods for balancing these needs have been used throughout the history of the three valleys and how do the results of those decisions affect contemporary water issues in Southern Nevada? What can we learn from a century of decision-making related to the conflict?

“The rapid increase in population in the Las Vegas Valley, beginning in 1941, caused an apparent critical water shortage there, and in Pahrump Valley increased agricultural development resulted in further exploitation of ground-water supplies. The purpose of the study upon which this report is based was to determine the occurrence, source, and amount of ground water available in the three valleys (Las Vegas, Pahrump, Indian Springs). Water levels have declined in the valley. They may be expected to continue to decline until the cones of depression in the piezometric or pressure-indicating surface, caused by withdrawal of water from wells and springs have grown sufficiently to intercept the amount of recharge necessary to balance the total withdrawals of ground water.”

Maxey and Jameson, Geology and Water resources of Las Vegas, Pahrump, and Indian Spring Valleys, Clark and Nye Counties, Nevada, 1948

Because the Water Company relied on what was at least initially an open and natural water supply flowing freely from springs, the risks of contamination were often a source of controversy between the city and the Water Company. While the company exercised what it considered due diligence in protecting and maintaining the water sources, the distance from the springs to the city and the exposure and vulnerability of the transmission lines were a cause of anxiety and frustration for Water Company officials and engineers, as outraged citizens complained to public health officials of frogs and lizards in their drinking water, and effluvia in the reservoirs. The railroad itself and public health officials regularly tested the water for contaminants.

For the most part the water supply was considered excellent if hard—the best in Nevada, according to one state official—and when piping water from Lake Mead to the city was publicly discussed after the war, one of the issues was the inferior quality of the water from Lake Mead.

“The largest cesspool in town and containing the human excretions of over 500 men daily, was on the 23nd and 23rd inst., emptied into the Las Vegas Creek, where a short distance below is located the fine herd of dairy cattle that supplies the milk for the citizens of Las Vegas. The cattle obtain all the water they drink from the creek . . . Near the slaughter house on the Las Vegas Ranch, is a fine lot of hogs that wallow in the water from the creek. The only supply of meat Las Vegas has is butchered in the slaughterhouse, and the meat must be washed with sewerage water . . “

J.T McWilliams, complaint to Clark County Commissioners, May 1912

I have made no comment, whatsoever, to anyone in connection to this paper, as the contents of same sound to me like absolute rot, but the non-thinking employee’s mind is being filled daily with such stuff as this . . .If it is not the water supply and the water mains, it is the sewer and septic tank business or something else in connection with the Company’s interests, and it is rather a hard battle to fight such things down, although they originated from a man of McWilliam’s caliber. . . I believe in this connection, as in all similar cases, the only thing to do is to absolutely say nothing and let matters work themselves out . . . “

Walter R. Bracken to H.I. Bettis, letter, May 24, 1912

“I anticipate trouble with him now for the next six months, or until the city sewer is completed or the location of the septic tank definitely decided. But in my opinion, being nothing but a foolish crank, I don’t think we should pay any attention to him, only to protect out rights when he brings such things up before the authorities.”

Walter R. Bracken to J. Ross Clark, letter, June 4, 1912

“I have made a careful investigation and find no good reason for complaint on the part of any citizen of this community . . . Las Vegas has never had a single case of sickness due to unsanitary culinary water, and I feel absolutely certain, there is no room for criticism at present regarding the Las Vegas Creek. If there was any excuse prior to two weeks ago, there is not now, as all defects have been remedied. The railroad has a great deal more at stake in this community than any other concern or individual, and I am sure would not knowingly do anything to endanger the health of the people living there.”

Dr. Roy Martin to the Nevada State Board of Health, letter, June 10, 1912

“I am sure that the railroad has done everything possible to maintain an adequate supply of pure water and to prevent any contamination that might result in unsanitary conditions there. . .”

Joseph Edward Stubbs, President of the University of Nevada, July 2, 1912

“The said reservoir is reported to be in a filthy and unclean condition, containing matter that tends to breed germs of disease. That the outlet from said reservoir into the pipes that convey the water top the water mains for distribution throughout the city is in such a state of decay that it allows frogs and other animal bodies to pass into said pipe and mains, and thus serve to pollute the water which is used in our homes for domestic use and drink. Therefore you are requested to give this matter your earliest and earnest attention . . . and make the said reservoir and source of water supply clean and free from impure matter when it enters said pipe and water mains.”

Henry M. Lillis, City Attorney, to Walter R. Bracken, letter, June 29, 1916

“The trouble has been temporarily corrected and the reservoir at present in good condition . . . there are now 3 screens and while they will have to be cleaned at least once a week, they will most certainly keep the frogs and filth from entering the main”

Bracken to H.C. Nutt, General Manager of the SP,LA & SL Railroad and President of the LVL&W Co., letter, August 2, 1916

“. . . it is imperative that something be done to improve the quality of the drinking water furnished to the citizens and employees at Las Vegas.”

Dr. Barr to Bracken, letter, July 14, 1916

“In this connection, we, of course, realize the importance of the water supply at Las Vegas, involving, as it does, the health of the entire community . . . I am arranging to ask for authority to put down an artesian well, which, together with the flow from Spring No. 1, we feel will give ample and pure water for the town of Las Vegas.”

W.H. Comstock to Governor J.G. Scrugham, letter, July 30, 1923

Inquiry:

What scientific advances in the mid- and late-1900s changed the definition of potable water and how have utility companies and the public responded to the increased knowledge?

“Roof over the reservoir, in my opinion is MOST ESSENTIAL . . All of our troubles in the past years with not only the state health department but with City and County officials were on account of the condition of the water which we held in the reservoir without being enclosed. The water, in time, even though with cement bottom, if exposed to sunlight, will become filled with moss and other growths and while this might not be injurious, yet to those using and drinking the water it will look not to be pure and healthy, and an uncovered reservoir is subject to much criticism. Migratory birds would always be using it, and to keep the town boys from using it as a swimming hole would be almost impossible.”

Walter R. Bracken to Howard C. Mann, Chief Engineer UP System, letter, April 26, 1928

“It is my opinion that the entire water supply should be chlorinated constantly as a safety measure, starting immediately.”

D.D. Carr, MD, Clark County Health official to A.M. Folger,letter, May 25, 1950

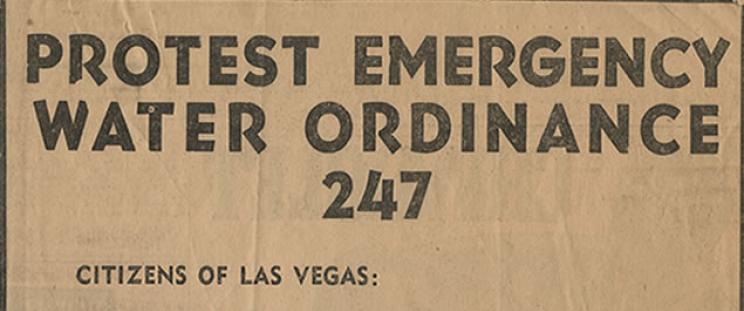

While the Las Vegas Springs enabled the railroad to establish a community in the Las Vegas Valley, it was still a community in a desert. The railroad owned the rights to, and controlled access to, all the water from the springs, and fiercely defended any encroachments on that water. So the discovery that drilling elsewhere in the valley could produce a heavy artesian flow set off a gold rush for water. Many believed that artesian water was inexhaustible, and even though Nevada’s water laws dictated that all water must be appropriated to beneficial use, many well-owners let their wells run freely rather than cap them and conserve the flow.

Because customer water meters were prohibited by state law, there was no mechanism for controlling an individual user’s water consumption. The profligate domestic use of water contributed to Las Vegas becoming the highest per-capita user of water in the state. Water usage increased even more when individuals and businesses began installing evaporative coolers.

The City of Las Vegas, which for a time proudly pictured a freely flowing artesian well on its letterhead, occasionally passed ordinances prohibiting the waste of water or proscribing lawn watering during certain times of the day. During particularly acute shortages, the police department would assign officers to enforce watering restrictions. Attempts by the Water Company to restrict water usage either by city ordinance or through the use of water meters were bitterly opposed by many in the city who accused the company of attempting to maximize its profits by limiting the amount of water it was willing to supply. As Las Vegas Review-Journal editor A. E. Cahlan commented on one of the Water Company’s many efforts to repeal the state law prohibiting water meters, “The threat of the use of meters is solely because of the hope of increased revenue with no improvement in service.”

“. . . chances are the principal cause of lack of pressure is the prodigal use of water in the town for irrigating purposes, etc., a situation which is very difficult to control . . . I am very skeptical of the advisability of purchasing somebody else’s wells . . . “

J.Ross Clark to W.H. Comstock, letter, May 25, 1920

Inquiry:

Knickerbocker states: "If we are unable to reasonably regulate the consumption of water, then it only means that the more there is available, the greater the consumption per capita will be . . ." What pre-1950 evidence exists to substantiate and refute his claim in terms of both public and private water uses?

“There is an abundance of water available for all the needs in the town of Las Vegas, if some reasonable effort is made to conserve it and to shut off sprinkling during the day time”

F.N. Knickerbocker to Walter Bracken, letter, July 8, 1935

“ . . . The decrease in production of water at Las Vegas is more or less disturbing. It seems to me that fact alone presents one of the strongest arguments you can make with the city officials, newspaper men, etc., as a reason and necessity for conserving water . . . I suggest you keep hammering away on the matter in Las Vegas, and I am sure you are bound to get some results. If we are unable to reasonably regulate the consumption of water, then it only means that the more there is available, the greater the consumption per capita will be . . . “

Knickerbocker to Bracken, letter, June 25, 1936

Inquiry:

Reverse-engineer air conditioners of the 1930s. Given only technology available at the time, what alternative designs might have proven more environmentally friendly, particularly in terms of water conservation and waste? What factors may have negated or supported use of these alternative designs?

“ . . . there is a prodigal use of water, particularly during the heated term when very high temperatures prevail. The low water pressure resulting from the gravity system . . . has a bearing upon the waste observable in sprinkling lawns; another removable item of loss has been seen in negligent operation of air conditioning apparatus, of which there is much in the city. From time to time the attention of the public has been directed by advertisements in the city newspapers to the waste of water by consumers, and such educational work will, it is hoped, produce lasting results. There is a city ordinance relating to the wasteful use of water, passed in July, 1939 but it has not been enforced . . .”

There has been a great deal of waste of water in the Las Vegas Valley, and in considerable measure this conditions persists. Until the wood stave pipes which quite recently underlaying the principal part of the city and several of its platted additions were replaced with cast iron pipe, the constantly recurring leaks in the mains accounted for a considerable loss of water both visible and annoying to the townspeople. Under the circumstances it must have been difficult to obtain serious regard to the company’s reiterated complaints concerning citizens who leave their lawn hose running all day and operate air conditioning devices with continuous streams of water throughout their waking hours.”

W.H. Hulsizer, Manager of Properties, UP, Omaha, Report on the Las Vegas Nevada Water Supply, March 25, 1942

Inquiry:

Analyze the locations of wells and their available acre-feet of water in the Las Vegas Valley during the 1940s. Considering geographic conditions such as soils, aquifer volumes, and average annual precipitation, what would constitute sustainable use of groundwater resources? How would this translate into private, public, and agricultural uses?

“Locally , much of the excessive decline of water levels in Las Vegas Valley has been a result of local overdevelopment caused by close spacing and heavy pumping of wells. However, the available data indicate that ground water probably is now being pumped from storage; that is more water is being taken from the reservoirs than is entering them from the recharge areas, and that therefore part of the water-level decline has resulted from over pumping. Thus, continued withdrawal of substantially more than 35,000 acre-feet of ground water annually will result in continued, and possibly increasing, decline of the water level and in overdevelopment of the ground-water supply in Las Vegas Valley.”

Maxey and Jameson, Geology and Water resources of Las Vegas, Pahrump, and Indian Spring Valleys, Clark and Nye Counties, Nevada, 1948

“I have a fight on my hands, and McWilliams threatens my Post Office position, but I am fighting for principle and the rights of the company and am not fearful of the threats of any crank . . .”

Walter Bracken to J. Ross Clark, letter, June 4, 1912

“I am trying my best to avoid any clashes with the local health authorities or City Commission.”

Bracken to E.E. Calvin, letter, July 10, 1923

“We are a public utility, and are under the direction of the Public Utilities Commission of Nevada. We are also operating under a twenty-five year franchise, and through advice from our Legal Department, we want to do everything we can to protect that Franchise, as it is a very liberal one for us.”

Walter Bracken to Eugene McAuliffe, President of the UP Water Co., Rock Springs Wyoming, letter, March 1, 1929

“The President [of the UP] now advised that as there is a surplus of water that can be used for domestic and city purposes when the growth of the city demands, it will not be necessary at this time to consider installation of meters involving considerable expenditures. He has reached the conclusion we should at as early a date as practicable take steps to obtain an INCREASE in the water rates . . . of 100% in the present flat rates; reserving however, the right to proceed with the installation of meters at a later date if such action becomes necessary to conserve the available supply . . . “

F.H. Knickerbocker to F.R. McNamee, letter, June 13, 1929

“Regarding some inquiry of the Nevada Public Service Commission of the operations of the Las Vegas Land and Water Company. I do not see that there is any action that should be taken at this time. Am interested, however, in knowing what the situation might be if some organization of citizens or others should make an effort to acquire by condemnation or otherwise, the water system of the LVL&W.”

Knickerbocker to E.E. Bennett, letter, October 14, 1934

“. . . I agree that there is nothing that we can do at this time, unless possibly a quiet campaign should be started to attempt to kill the proposed action.”

Bennett to Knickerbocker, letter, October 20, 1934

“Article in Labor correct, except proposal on ballot referred only to powers system. At recent city election entire board running on platform vigorously advocating municipal ownership both light and water facilities and since their installation June 1 still active in same cause. . . efforts made did not prevent election these candidates. . . Am advised board applied to PWA [Public Works Administration]for $200,000 loan for municipal water system, but was able to block this for time being thru PWA officials Reno. “

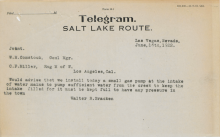

Walter Bracken to W.M. Jeffers, coded telegram, June 6, 1935

“There is no doubt that we should secure remedial legislation at the next session of the legislature. As a matter of fact we endeavored to do that at the last session and you will recall that the attempt died on the vine due to certain representations of the Las Vegas people which I understand they have not kept. I believe the present law [prohibiting customer water meters] could be repealed, but if not I see no reason why it could not be amended so as to permit meters on commercial and industrial properties . . “

E.E. Bennet to F.H. Knickerbocker, letter, June 27, 1936

“I recommend that the LVL&W Co. continue to own and use at present its water distribution system, for the reason that operations are carried on with a substantial measure of profit, and indications are that this condition will continue . . The day may come when we should sell our plant to the city of Las Vegas, but that time has not arrived. Our water rates are reasonable; our present service appears to satisfy, and so long as we continue our recent policy of extending distribution mains wherever reasonable inducement offers, municipal ownership is not likely to become a pressing issue. Neither the city nor ourselves would benefit from municipal ownership under existing conditions. . . Maintenance of friendly relations with the city officers and leading men of Las Vegas should be made an unvarying rule in order to prevent causes of irritation as far as possible . . . ”

W.H. Hulsizer, Manager of Properties, UP, Omaha, Report on the Las Vegas Nevada Water Supply, March 25, 1942

“petitions are now being circulated in Las Vegas authorizing creation of the Las Vegas Valley Water District, as outlined in the newspaper clipping I sent you October 17 . . At the Rotary meeting today, attended by about 100 principal businessmen of the town, Archie Grant circulated one of the petitions and made an explanatory speech . . . and stated that development here would be definitely limited without the creation of this Water District, as the Union Pacific had stated it was not interested in bringing water from Lake Mead.“

A.M. Folger to Frank Strong, letter, November 6, 1947

“ . . . Unless it can be shown that Union Pacific would be damaged by completion of the Water District, I am opposed to our taking any position in the matter as it is my opinion that the value to Union Pacific of a continuing development in the area would be much greater than the revenue we are presently earning from the water utility, and in any case, even if it should later be found necessary or advisable for us to oppose the development of the water district, I think this could be accomplished without our appearing too prominently in the matter. . . I strongly recommend that we keep hands off of this argument until such time as the development of the plan indicates clearly where our best interests lie . . I suggest that your reply to Mr. Cragin’s letter be noncommittal as far as any suggestions as to what action the city should take, perhaps advising him that we are of course vitally interested in the development of the area and that it is our desire to assist all possible in any activity which would tend to expand the industrial and other developments.”

William Reinhardt, Vice President UP System to G.F. Ashby, telegram, October 11, 1948

Inquiry:

What interactions and interests existed between the Las Vegas Land and Water Company and Union Pacific in terms of policy, legislation, economics, and diplomacy and what were the positive and negative ramifications of those interactions?

“[Mayor Cragin] stated his policy in the past, whenever the question of municipal ownership of water or power facilities arose, had been to discourage it because while it might work alright at first, it eventually became a political football, to the detriment of the community. . .we feel that we should avoid taking sides in the controversy, as nothing can be gained by making enemies of either the County or City officials. However in replying to Mayor Cragin you may wish to advise him that we concur in his thought that water produced in the city should be used in the City, and in fact that has been the policy of the Water Company.”

A.M. Folger to F.G. Ashby, letter, October 11, 1948

“ . . . While our company has thus far maintained an attitude of neutrality, considerable opposition to the plan has developed on part of some of our local citizens because of the vagueness of the costs, the quality of the water from the lake, and a reluctance to permit water produced within the city limits to be used outside the city limits to supply gambling resorts on “The Strip” south of the city limits.”

Folger to W.F. Harp, letter, June 18, 1949

The economic fortunes of the railroad’s Land and Water Company and the growing town, were inextricably bound together although their interests often diverged, and sometimes clashed, sometimes openly and in public. The Union Pacific Railroad, through the Water Company, was truly committed to providing the city with adequate and pure water at a reasonable cost. But as the cost of constructing, maintaining, and extending the water system to outlying subdivisions and districts and industrial tracts rose, and the demands on a limited natural water supply increased, these clashes became sharper, as the private interests of the railroad were seen by the city often as too conservative and unresponsive while the railroad perceived profligate water use, waste, and over-extension of water lines simply for the profit of ‘wild cat’ real estate speculators and housing developers. There was truth in both view points. The railroad was fiscally conservative and the town and its developers were making excessive demands on a limited system with a declining natural supply of water.

Inquiry:

Considering the boom and bust cycles common in Southern Nevada, did the end of the railroad monopoly suggest anything about Las Vegas and its surrounding communities?

Matters came to a head after the construction and population boom of the Second World War, when the railroad, townspeople, and scientists acknowledged the water shortage and the inadequacy of the ground water supply and distribution system to support the growth the city was promoting. The cries for public ownership of the water system which rose occasionally in times of acute water shortages, became politically viable when in 1947 the Nevada Legislature passed enabling legislation for the creation of a “Water District’ in the Las Vegas Valley with the intention of augmenting the Water Company’s water supply from springs and wells, with access to Lake Mead. Making the water district a reality took time and tortuous negotiations both through public meetings, petitions, elections and the passing of public bond issues as well as agreements with the railroad for the appraisal and sale of its facilities. In 1954, The Las Vegas Valley Water District formally took possession of the Land and Water Company system, ending an era of railroad monopoly.

As educators stretch to find ways to prepare students for the 21st century, they learn that deep thought, analysis, interpretation, and creativity are critical to future success. Researchers regularly practice these behaviors and are exceedingly aware that the best way to learn is to delve head-first into topics. They begin by reading works of others to gain a basic understanding of the topic. This is called relying on "secondary" or "tertiary" sources. Eventually, researchers want to learn the truth behind what others have written... they want to interact with original sources, called "primary sources," and form independent conclusions.

Today's libraries are offering just this type of research opportunity to their users. Educators can engage students as they seek answers from original sources and help students decide whether their conclusions match those in textbooks and other authoritative resources.

For Teachers Only!

We've put together some starting points for using this digital collection to engage your students.

What's in this Collection?

This collection offers an incredibly diverse range of media. From pictures to technical reports and maps to letters, the collection tells the story of early Las Vegas and its surrounding communities. It uses contracts, newspapers, postcards, licenses, meeting minutes, and charts to communicate about the events that shaped Southern Nevada in terms of its water resources and uses. Reports, legislation, books, and flyers dot the archives of this collection to provide a snapshot of conflicts and resolutions that shaped today's water issues.

For the geographer, the collection addresses natural phenomenon such as floods, geologic compositions of specific parts of the Las Vegas Valley, and sizes and volumes of artesian basins hidden below the desert's caliche-hardened surface. Political scientists will find the collection's access to resources about water metering, public voice against conglomerate ownership, and diplomatic relationships among citizens and community leaders particularly enticing. The environmentalist will enjoy the collection's mass of resources showing the juxtaposition of public and private views of water availability. Civil engineers will get their hands dirty with city designs destined to succeed or fail based on finding wells and managing post-war population and resource shifts. And, the historian will find the excitement of the western frontier hidden in stories about early Nevadan cowboys, miners, and settlers.

How Can I Use This Collection?

Inquiry Questions

Educational resources appear throughout the collection to assist independent learners as well as educators. Near contextual overviews, embedded questions entice learners to explore the collection. The intention of these inquiry opportunities is to invite the collection’s visitors to go beyond a simple search-and-find method of seeking specific artifacts, instead viewing the collection as a complex collection of interwoven stories to be discovered and debated.

Timeline

The timeline provides extensive encyclopedic resources including simple-language explanations of events, eras, and people, teaching suggestions, questions for classroom discussion or individual assignment, and links to sources both inside and out of the Historic Landscape of Nevada collection.

Introduction to Collection's Content

To start using the collection, visitors should visit the "Getting to Know the Collection" section where they will explore artifacts and water-related topics while honing their knowledge of and skills for using the site’s metadata.

Primary Source Sets

Those seeking quick explanations of certain topics or teachers hoping to focus on a specific unit of study may want to take advantage of the site's primary source sets. These sets provide an overview of single topics. For each, there is a pre-selected collection of annotated artifacts relating to that topic, and teacher suggestions for using the kit within educational contexts.

Enjoy exploring. Discover a part of your history that you never knew. Find a meaningful gem that changes the way you think. And let us know what you think!

Need some ideas for how you might want to use this collection to engage your students?

- Have each student choose three inquiry questions accompanying the contextual narratives. Give students from several weeks to one semester to work on the questions and have them be prepared to give a verbal presentation on all three questions. On a pre-selected day, have each student provide you with his/her three questions. You select one of the three and that student has five minutes to present on the topic.

- Assign the "Getting to Know the Collection" activity to students. Upon completion, they should write their own "Get to Know the Collection" questions. Have students submit both their questions and the correct answers.

- In pairs, have students create a project (e.g., Virtual Museum, video) addressing one of the primary source set topics.

- Assign students a ten-year period within the timeline. Using the pre-existing nodes as the basis, have them add an additional ten nodes for their decade. These nodes should include information from both within and outside of the collection.

Like no other time in history, we now have immediate access to resources beyond what our human minds can fathom. From fact to fiction, information bombards our desktops and interpretations of information abound. With this gluttony of resources, there is a need for individuals to make educated decisions about information accuracy; and, when subjectivity exists, the intelligent consumer of information must also question the accuracy of those interpretations.

Today, libraries around the world are providing increased online, global, access to their resources. In an attempt to offer an unbiased perspective of Nevada's history, this digital collection provides visitors with access to a wide range of original sources. Providing only basic information for background understanding, this website leaves you, the user, to determine what interpretations may be correct and which may be questionable. UNLV's digitized resources, including the Historic Landscape of Nevada collection as well as myriad others such as the Southern Nevada: The Boomtown Years, Showgirls, Menus: The Art of Dining, and Welcome Home: Howard collections provide visitors with digitized images of primary sources. With these, the student of history can analyze and interpret the resources without intervening influences.

What is a digitized collection?

A digitized collection is a group of historical artifacts whose images have been scanned and saved in digital formats. This collection stores items related to the theme of the history of water in Las Vegas and surrounding valleys using high-resolution portable document formats (PDFs). This format allows users to remotely view the artifacts instead of requiring they hold them in their own hands. In some cases, digitized copies allow viewers to magnify items to the point that they may see more onscreen than would be possible looking at the original with the naked eye.

A Primer—Water in Southern Nevada

How are digitized collections organized?

Though digitized collections generally revolve around a single theme, they include numerous other collections within them. For example, the Historic Landscape of Nevada includes artifacts from Helen Stewart's personal photo collection as well as artifacts from the Union Pacific's official records. These collection subsets all contribute to the main collection's theme—water issues in the history of Las Vegas and its surrounding valleys.

The Historic Landscape of Nevada offers a unique and rich collection of resources. Its content crosses many fields of study while addressing a topic that is paramount to human survival—water. Nowhere is this topic more important than in arid regions on Earth, precisely where Southern Nevada residents find their homes. Lying in the rain shadows of both the Rocky and Sierra Nevada Mountains, the Great Basin encompasses numerous deserts including the Mojave of Southern Nevada, Southern California, and Northern Arizona. Amidst what is often seen as barren and desolate land is a desert oasis—Las Vegas, a Spanish phrase meaning "the meadows."

That's exactly what early explorers to the area that would become Southern Nevada found. Tucked away in a valley of low-lying mountains was a spring-fed region unlike any for miles around. Though few wanted to live there, it was a place where travelers would surely need to rest on their long and arduous journeys across the new nation. Pioneers had to stop on their way to find gold and farm the lush agricultural lands of California.

What is metadata?

A constant problem in the world of information is the difficulty of accessing specific resources. Librarians combat this problem using "metadata," otherwise known as “data about data.” They assign terms to information bits so users can easily retrieve specific items. For example, a picture of Lake Mead encroaching St. Thomas might include metadata terms such as "aerial photograph," "cities and towns," "St. Thomas," "floods," "buildings," "trees," and "water-saturated sites." These metadata allow users to search the collection by any of these relevant terms. It is the same concept as "tagging," the term used in the general computing community. Using this system, librarians can code reports, maps, charts, correspondence, envelopes, legislative affairs, and more.

Capitalizing on the need for a way station in the desert, several parties sought to inhabit and tame "the meadows." First came the Mormons and their still-standing fort from 1855. After a brief tenure in the area and difficulties with local Paiutes, they abandoned the fort. Next came Octavius Gass, a miner and politician, in 1865. Upon defaulting on a loan to Archibald Stewart, he, and eventually his widowed wife, Helen, became proprietors of the land. Their hard work and dedication to the area earned Helen Stewart the title "first lady of Las Vegas" and it was with their land and water rights that Las Vegas had its true beginnings. The railroads followed the miners and, before long, Las Vegas and its surrounding valleys were booming. Las Vegas was not just a way station, but a town in its own right.

Because of the free flowing creeks coming from profligate natural springs, the early town thrived. Assuming the aquifers provided an endless supply of water, there were no concerns about the possibilities available in the new western town. Before too long, though, doubts and concerns began to interrupt the plans of entrepreneurs. That became the beginning of conflict. How much water was available in the valley? Who should control it? For what purposes could it be used? These questions provide the foundation of this digitized collection.

Let's get to know this collection...

- Find a picture of Las Vegas from 1881 and one from 1920 and one from 1974. What can you deduce from the photographs? What could you conclude about water resources in the region based solely on the pictures? [Hint: Do a search for terms including "Las Vegas," "aerial photographs," "1920," and "1974."]

- What five adjectives would you use to describe the relationship between the Las Vegas Land & Water Company and the Los Angeles, San Pedro, and Salt Lake Railroad between 1905 and 1930? [Hint: Triangulate information from the timeline, "Walter Bracken" contextual overview, and correspondence resulting from a search of the terms "Correspondence," "Las Vegas Land & Water Company," and "Los Angeles, San Pedro, and Salt Lake Railroad" using the Boolean search term "AND" to link concepts.]

- Create a timeline showing the state of the Lost City before, during, and after the completion of Hoover Dam. [Hint: Read the contextual narrative about Floods and do searches for "Bonelli's Landing and Fort Corvallis/St. Thomas, and Lost City" and review the following artifacts.]

- Review six artifacts on the topic of soil conservation projects in Southern Nevada. Summarize your findings into a single paragraph. [Hint: Do a search on the topic "Soil Conservation Projects."]

- Using items from the collection that were written for the public citizens of Las Vegas, what image would you infer Las Vegas leaders attempted to project when promoting the city and its water resources? [Hint: Look for a newspaper clipping, leaflet, brochure, or press release in the collection and click on the links in the record to get to additional items from the various news and publicity formats.]

- Read and plan how to answer one of the inquiry questions embedded in this site. [Hint: Look next to each of the contextual overviews to choose a question.]

- Scan the artifacts in two of the primary source kits. Which kit do you feel provides a better overview of the conflicts Southern Nevada experienced in terms of water availability and use? Justify your response.

- Prepare brief biographies of eight people important to the history of Southern Nevada's water issues. [Hint: Use information available within the timeline.]

- In what parts of the Las Vegas Valley have private or public entities drilled wells? [Hint: Do an search for the terms related to water. By narrowing terms and looking for synonyms many items should be retrieved. Suggested topics like "Wells," "Water Well Drilling, "Boring," "Wells—Law and Legislation," Wells—Design and Construction," and "Pumping Stations—Design and Construction" can then be combined with the term "Maps."]

- What roles did the Basic Magnesium Plant play in the story of water in Southern Nevada? [Hint: Do a search on the topic "Magnesium—Industry and Trade."]

What are primary sources?

Primary sources are artifacts resulting from direct personal experience with a time or event. The benefit of using primary sources is that they provide a first-hand account of a person or event that can then provide evidence of that given historical era. Examples include diaries, art, autobiographies, interviews, letters, music, photographs, and speeches.

Primary sources are the cornerstone of historical study. When "real historians" seek to understand the past, they may begin by reading third-party accounts of events, but, ultimately, they go directly to the source of their content. This is because primary sources explain and characterize events and relationships during the time they happened. While students of history may understand a historical era from a retrospective point of view, they must also recognize that the decisions and thoughts of actors during those events occurred in real time. Those living the history in question did not have the advantages of hindsight that we have today. True historians seek to understand historical events within the context in which they occurred.

For these reasons, this website includes general, third-party overviews of events and people that shaped the history of Southern Nevada in terms of water as well as the related primary sources. Like the timeline, the overviews provide context for those who are new to topics within the collection. The artifacts themselves allow advanced and detailed study of those topics. For some who are new to the topic, however, knowing where to begin with the artifacts may prove a daunting task. Therefore, the section includes several "primary source sets." Each set includes sub-collections of artifacts related to single topics.

What are secondary sources?