"Access to archival materials stored in LASR may be limited at this time."

Search the Special Collections and Archives Portal

Welcome Home Howard

Whatever Became of the Daring Aviator

If the desire to gamble yourself into insolvency should ever take you to the improbable town of Las Vegas, Nevada, you are very likely one day to come across the following scene:

You will see a lean, weary man, six feet three inches tall, dressed in dark nondescript trousers and a white shirt open at the throat, glumly eating steak and salad at a table in the bar of a gaudy hotel. Surrounded by an atmosphere of high-living and wealth, he will look as if he hasn't two silver dollars to rub against one another in his pocket...

The man is Howard Robard Hughes. You may be sure it is no other. There is only one Howard Hughes.

A few weeks ago, in Las Vegas , a woman approached Hughes's table with her eight-year old daughter, and asked him for his autograph. As Hughes amiably scribbled it out she said gratefully, "My daughter will be so happy to have the autograph of the man who employs all those famous actresses." Hughes finished writing then followed the woman with his eyes until she disappeared in the crowd. "I wonder," he said pensively, "whatever became of Howard Hughes, the daring aviator?"

Draft of Stephen White's, "The Howard Hughes Story," published in Look Magazine, February 9, 1954. UNLV Special Collections, Howard Hughes Collection...

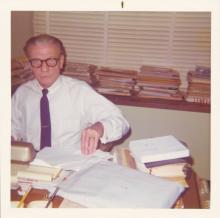

Carl Byoir and Associates, a large Los Angeles public relations firm, numbered among its accounts prominent celebrities and corporations, but the firm’s most challenging and demanding client was no doubt Howard Hughes. In 1996, Special Collections acquired from the Howard Hughes Corporation in Las Vegas the Hughes account and reference files of Dick Hannah, the Byoir Vice President and account executive who handled Howard Hughes’s publicity. Like other Hughes agents, Hannah did far more than his title would imply. He not only directed public relations by drafting countless news releases and preparing mountains of press kits with sets of “authorized” photos, he gathered enormous amounts of information concerning what was written about Hughes or about subjects in which Hughes had interest. Hannah’s job for Hughes was to control the public image of Howard Hughes and his far-flung business and political interests, and to monitor the press for any report of Hughes himself or of anything in which he might have an interest or feel threatened.

The timesheets, which Hannah carefully prepared for billing, document his multifarious and sometimes unconventional activities on behalf of his client:

December, 1950: "Activities on behalf of Hughes Tool Company in connection with reading, clipping, and filing articles appearing in newspapers, general magazines, and trade periodicals; obtaining and analyzing pertinent reports published by government and private sources."

December 18, 1950: "Working with national magazine pulling through article on bachelors, making sure Mr. Hughes would get proper full-page first in layout position and was favorably represented."

January 24 and 26, 1950: "Preparation of a report on the sponsorship, activities and reputation of a woman's organization, at request of client."

April 19, 20, 23, 1951: "Preparing a special report on the activities, reputation and financial support given the National Association of Colored People, at request of client."

November, 1951: "Working with editors of a national news magazine concerning one of their writers and the general, over all management of the magazine. Relaying information to the west coast."

April 1, 1952: "Working with editorial writer of New York daily newspaper on background material for an editorial on Mr. Hughes's fight against communism in the motion picture industry."

July 24-25, 28, 1952 - 8 hours: "At request of account, checking back-issue newspapers for reviews of a certain musical show, and sending a report to the west coast."

In 1968 Hannah's report on the Hughes Account had a heading "Special Work for Hughes Office -- Purpose: This includes a great many miscellaneous matters, some important some not so important but regarded by Howard Hughes as the most important function we perform."

The September 1970 report stated: "Hannah has been spending good portion of time handling 'special research projects' for client execs, notable Bill Gay, and to a lesser degree recently Bob Maheu. These involve tracking down a wide variety of rumors, keeping on top of lawsuits and possible lawsuits (usually with Chester Davis), and working on diverse matters at client request, some of which defy brief description . . ."

February 25, 1972: "Screening one hour version of 1970 Master's Golf Tournament to ascertain occurrence of specific incident as to play by Jack Nichlaus at client's request. Double checking all Nichlaus sequences in final round of tournament; notifying client representative as to findings."

This collection of over 100 cubic feet is the single most comprehensive collection documenting the press coverage of Hughes, and how that coverage was managed and controlled. But beyond that, as an integral part of Hughes enormous information-collecting operation, it also documents what interested Hughes. The collection also contains most of the official Howard Hughes photographs which Hughes authorized for use by his public relations machine. It was one of the many paradoxes of Howard Hughes that a man so paranoid and obsessed with avoiding the public eye was such a master of public relations. Not since Louis XIV has a public figure gone to such lengths to control the public's perception of himself.

The most immediately revealing and compelling documentation of Howard Hughes's Las Vegas years remains the mysterious trunk of memos, which form the basis of Michael Drosnin's Citizen Hughes. The documentation left by Dick Hannah, on the other hand, is less revealing of Hughes the man, but reveals much about the Hughes operation, driven by paranoia and the compulsion to know and to control. Hannah's operation monitored and analyzed the press and public perception, and devised the spin. Much of it is simply the grist of the clipping services: boxes of clippings on the construction and "flight" of the Spruce Goose, or publicity for Hughes's RKO films. There are also files on the Las Vegas properties, and press reports on things that might affect or threaten Hughes -- from the Atomic Energy Commission; to Clifford Irving; to the Mafia; to the Watergate Hearings; to any writer, journalist, or television producer who attempted to portray Howard Hughes. One of Hannah's most problematic challenges was the persistent rumor that his client was in fact dead.

The Maheu affair generated boxes of files in Hannah's office. The coup that ousted Robert Maheu from head of Hughes's Nevada Operation generated lawsuits and countersuits for libel and intensified the interest in the press about Hughes mysterious Nevada Operation. In the files are annotated transcripts of depositions, press conferences, and from the "60 Minutes" program in which Morley Shafer investigated why the Hughes Las Vegas properties were losing money. Who was stealing from whom within the Hughes camp was a compelling news story, almost as compelling as Watergate and Hughes's connections with Bebe Rebozo. As the Byzantine maneuvers for control of the Hughes Empire unfolded, Dick Hannah quietly carried on his business.

Control of the Hughes Image reached bizarre proportions when Chester Davis, Hughes's Wall Street lawyer, vice president and chief counsel for Hughes Tool Company, created Rosemont Enterprises, Inc., a Hughes subsidiary whose sole purpose was to control all literary material past, present, and future about Howard Hughes. Staff were hired who located and inventoried all known stories published about Hughes anywhere, or any newsreel footage that existed. They tried to acquire exclusive rights over all footage and photographs. Through a network of informants, any writer researching or writing a piece on Hughes was reported to the Rosemont 'office,' in other words, to Bill Gay at the Romaine Street headquarters in Los Angeles. The writer would be investigated, contacted, informed that Rosemont had been granted by Hughes exclusive rights to his image and biography and would offer payment to the writer for exclusive rights to 'develop and exploit' the writer's material. If a writer could not be bought off, lawsuits were threatened against writer, editor and publisher. The Rosemont files contain investigative reports on a number of journalists as well as a number of unpublished pieces, some transparently fictionalized, about Hughes, for which the writer had accepted payment from Rosemont. Acquisition was not really intended for development, but for suppression.

The extent to which Hughes would go to suppress stories about himself and how violently he hated such intrusions into his privacy can be illustrated by his handling of a story Life Magazine ran on him in 1962. Hughes was at the time enmeshed in litigation over his handling of TWA Airlines, and was particularly sensitive about publicity, although he was willing to offer to the magazine interviews by members of his staff and even his wife, Jean Peters, as a ploy to postpone or control the spin of the story. He sent his lawyer Guy Bautzer, his PR agent Dick Hannah, and a very influential Washington lawyer named Clark Clifford to 'discuss' the story with the magazine and try to convince the magazine to kill the story or at least allow Hughes final approval. Life magazine was not to be intimidated by Mr. Hughes and the story ran. Afterwards Clark Clifford somewhat disingenuously offered his opinion that the story was "helpful," although Robert Maheu, who forwarded Clifford's letter to Bill Gay, did not agree. The failure of his agents to quash the story infuriated Hughes, who vented his anger on Guy Bautzer, a suave big name Hollywood attorney who was probably used to his client's outbursts.

"Please give me an immediate brief reply to each of these points," Hughes wrote to Bautzer, "but let me say beforehand I desire a conversation with you this weekend, which I hope can be in person, and the purpose of this conversation will be to work out a better understanding between us. From the looks of things, it would be difficult to conceive how we could have brought our present relationship to a much more bitter and antagonistic status, I was so upset following our last conversation before my health commenced to recover from the ill effects of my loss of temper and explosion of blood pressure it brought our conversation to a conclusion. I am sure that, like everyone else, it is my tendency to see controversial matters from my side, but perhaps it is your nature, likewise, to look at things from your side.

Now I criticize you for seeming to be more interested in the management of Northeast Airlines than in anything else. You again answer, 'I am doing a great job.' What good is a great job to me if it benefits Northeast Airlines, which I may only possess for another month at most and when Northeast Airlines is not the place where I desire you to direct your efforts when it is Life Magazine and three or four other situations which are cutting into my body like a knife and destroying my efforts to recover my health and putting me daily closer to the grave with unbelievable rapidity and force. Your great job for Northeast Airlines might as well be a great job for Henry Kaiser in Honolulu, when I am about to be crucified and I would say it is an even money bet that they will cause Jean {Peters, a.k.a. Mrs. Howard Hughes] to take the same route as Marilyn Monroe.

Under these circumstances you may understand why even one minute of effort on your part devoted to Northeast Airlines evokes my extreme bitterness when I feel that time and that effort should have gone to Life Magazine.

I await your reply. I don't know if I will be able to answer this morning as I am about at the end of a rope."

In Las Vegas

"I like to think of Las Vegas in terms of well-dressed man in a dinner jacket, and a furred female getting out of an expensive car. I think that is what the people expect here -- to rub shoulders with V.I.P.'s and stars. Possibly dressed in sports clothes, but if so, at least in good sports clothes. I don't think we should permit this place to degrade into a freak or amusement park category, like Coney Island.

Bob, there are almost ten new hotels announced. The one that troubles me the most is the new Holiday Inn right smack in front of the Sands. To make it much worse, they are planning to make it a Showboat sitting in a huge lake of water. A Showboat with a pond of stagnant infested water. If they are considering using water from Lake Mead, the effluent in the water would smell to high heaven. Jesus! When I think of that lake of sewage disposed on the front lawn of the Sands. Ugh! It may even smell up our Sands Golf Course. Whatever the sources of the water, there would is the additional problem of mosquitoes. They would not be able to have water running in and out, so it would become stagnant and an ideal place to breed mosquitos. If this crumby hotel cannot be stopped, I would just as soon sell at a loss the Sands..."

Memos from Howard Hughes to Robert Maheu, 1967, quoted by Michael Drosnin in Citizen Hughes, pp.107-108

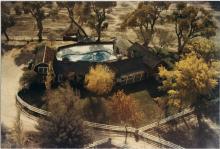

When Howard Hughes slipped into Las Vegas on a special Union Pacific train on the night of November 27, 1966, and took up his bizarre residence on the top floor of the Desert Inn, Hughes had already become an eccentric and increasingly mysterious recluse. Although he continued to play monopoly with his companies and fortune through an army of dedicated agents and aids, his public career as a celebrity -- the great Industrialist-Aviator-Movie Producer -- was over.

Howard Hughes did not build a thing in Las Vegas; in fact he was spooked by the city. His idea of Las Vegas was the movie set for his 1952 production of The Las Vegas Story with Jane Russell, Victor Mature, and Vincent Price. He had used the Flamingo, as Alan Hess recounts, "to represent all that was glamorous and exciting about Las Vegas . . . as the example of grandeur and the luxury of plush gambling on the Las Vegas Strip." That was the Las Vegas that the delusional Howard Hughes returned to in 1966, to hide from subpoenas and the media, and to build an empire in the desert. But by 1966 the glamour world of the Flamingo was a delusion from the past. Hughes was living another reality in 1966 controlled by a cohort of Mormon advisors, communicating with his lieutenants, even the chief of his Nevada Operations, via memo. Hughes was horrified by what he would have glimpsed from his penthouse windows had they not been permanently covered to shield him from the dangerous sunlight and germs. Circus Circus was bringing Coney Island next door, and his nemesis, the federal government, was shaking his penthouse by testing nuclear devices just down the highway. To the paranoid Hughes, Las Vegas had become a place of Fear and Loathing.

Hughes had purchased the Desert Inn, as the story goes, because he couldn't get a room there, and took over the top floor. He then proceeded to purchase the Sands, the Frontier, the Silver Slipper, and that monument to failed dreams, the Landmark, with its space-needle saucer-on-a-stick. Hughes is credited with bringing corporate legitimacy to Las Vegas, and running out the Mafia. The State of Nevada did oblige Hughes by changing its gaming licensing laws for him, thereby ushering into Las Vegas publicly traded hotel corporation like Hilton and Marriott, who changed the face of Las Vegas and whose hotels looked like hotels and corporate towers, not like roadside motels with big signs.

Under Hughes, or Hughes's people, his hotels continued business as usual, and for all intents and purposes under their previous management. Moe Dalitz still ran the Desert Inn, Jack Entratter and Carl Cohen, the Sands. The story was that people like Dalitz and Entratter were tired of Bobby Kennedy's Justice Department's relentless investigations of their business associates and decided to sell out to Hughes. But the economic changes that were affecting Las Vegas hotels and driving the expansion of convention centers and room additions would have occurred without Hughes. How Hughes's people marketed their hotels as tourist, convention and entertainment centers was no different than what other hotels were doing, or from what Hughes properties had been doing before he took them over.

Hughes contribution to the Las Vegas Casino world was the opening of the troubled Landmark property as a casino. Originally built as an apartment building, the Landmark had struggled with financing, purpose, and location. The Hughes properties turned out not to be the spectacular success that some had expected (and hoped) was inevitable of any Hughes enterprise. The Frontier, like the Sands, was already being completely revamped by 1967, dropping its original western theme and joining the new Sands on a renovated Strip. The Silver Slipper remained notable mostly for its YESCO sign, a giant pop art silver slipper. A planned mega-4000 room expansion for the Sands never materialized. It was for Sheldon Adelson to completely re-do the Sands -- in fact by blowing it up -- to make way for the Venetian; the only part he kept was the Sands Expo/Convention Center.

His hotels were not the most profitable part of Hughes's Nevada Operation, and were unloaded after Hughes skipped town in 1970, to die soon after. The fact that the Hughes Corporation owned significant chunks of the Las Vegas valley, to be developed by its Summerlin Corporation subsidiary, was the lasting legacy of Howard Hughes in Las Vegas: master planned communities within a master planned community where even Howard Hughes might have felt safe from the horrors of the Strip and the Test Site.

Hughes fled Las Vegas, haunted perhaps by the Merry-Go-Round of Circus Circus; the Circus Circus, about which Hunter S. Thompson in his drug apocalypse, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, said "is what the whole hep world would be doing on Saturday night if the Nazis had won the war." But to Hughes it meant kids. Hughes described this apocalypse in his own words in a memo:

"The aspect of the Circus that has me disturbed is the popcorn, peanuts, and kids side of it… And also the Carnival Freaks and Animal side of it . . . In other words the poor dirty, shoddy side of Circus life. The dirt floor, sawdust and elephants. The part of a circus that is associated with the poor boys in town, the hobo clowns, and, I repeat, the animals. The part of the circus that is synonymous with the common poor -- with the freckled faced kids, the roustabouts driving the stakes with three men and three sledgehammers…"

His presence in Las Vegas needs more explanation than he is willing to give. Since the beginning of this year he has made his home in a series of austere single rooms at the Flamingo Hotel in Las Vegas , flying his private plane to Los Angeles only when his presence there is absolutely essential…

In a resort city that consists essentially of a strip two-and-one-half miles long and a few hundred yards wide, Hughes manages to keep himself almost completely inaccessible. His hotel room telephone is permanently plugged; his private numbers are closely guarded secrets

Hughes: I don't like this on account of the residence deal. There is going to be a hearing next month as to the validity of my Las Vegas residence. We have a whole set up to submit. Just say that the numbers are a closely guarded secret.

Then too it is no secret that he has invested heavily in Las Vegas land, and perhaps plans construction of some major division of Hughes Aircraft. The land is relatively cheap, the climate is perfect for flying and the terrain for airstrips, and power is available from nearby Hoover Dam. Hughes is mum on the subject

Hughes: Strike out "invested heavily" and the rest of the sentence after "land" - I'm not going to do that. This sort of rumor has caused a lot of real estate flurries already and if it is in print the real estate men will make more of it than they have. I don't want that. Can't you say, "purchased some land" instead of "invested," and the rest of it is misleading.

White: I won't quite do that - but I will say it has been rumored he will build a plant.

Hughes: Will you say "purchased" instead of "invested"?

White: I will say "bought"

Hughes: About the construction will upset my employees at the aircraft. If I deny it, then I have to give the reason for it. I think there were rumors a year ago but they are dormant now. If you awaken them, I will make enemies in Las Vegas .

Crisp Bacon

(1) crisp bacon, and milk... (2) v-8 juice... small can

Hughes: Strike out "crisp", I don't like it crisp. And be sure to strike out "milk". That is another thing that has hounded me all my life, like the tennis shoes. I never drink milk - well, I might with apple pie or hot cakes, but I very seldom eat those foods.

White: What do you drink?

Hughes: V-8 juice and water with my meals. (2) I don't like it out of a can that has been opened a long time, so if they use a small can then I am sure it is fresh. However I don't care if they pour it out of a gallon can, if they have just opened the can.

Hughes Aircraft and Electronics

"The trouble with my life is that I do not think I am cut out to sit behind a desk. I would probably be much happier if I were a pilot working for some small airline simply trying to do my job as well as possible. But, of course, such a thing could never happen because when you become wound up in the web of industry to the extent that I am unfortunately you just can't resign the way you can from a country club."

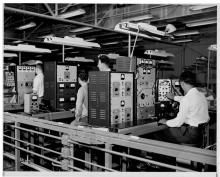

Hughes Electronics was the child of Howard Hughes the Aviator, as opposed to Howard Hughes Movie or Hotel/Casino Mogul. In 2003, Special Collections received from Hughes Electronics Corporation their corporate archives.

Howard Hughes took over control of Hughes Tool Company in 1924 at the age of 19, after his father's death. In 1932 he formed Hughes Aircraft as a division of Hughes Tool Company, essentially to keep track of the expenses of his personal interest in flying and aircraft. This personal passion for flying and developing experimental aircraft established Hughes as a celebrity test and racing pilot, as he set one speed record after another. His company won defense contracts during the war to develop high speed pursuit and reconnaissance aircraft and communication systems, most of which never went beyond prototypes and never entered production. Perhaps the most famous of these experimental prototypes was the HK- 1 Flying Boat, better known as the 'Spruce Goose', the gargantuan wooden cargo plane that Hughes himself piloted on its brief and only flight of one mile, 70 feet above Long Beach Harbor in 1947. Also in that year, and of far greater and lasting importance, the Radio Department of Hughes Aircraft formally morphed into the Electronics Department, where the future of Hughes engineering lay.

Hughes had attracted a number of stellar engineers and scientists from Cal Tech to lead his research and development teams headquartered in a plant in Culver City, California. But by 1953 most of his top management team had walked out, citing difficulties in working with Hughes, whom they characterized as an obsessively controlling, albeit hopelessly indecisive, micromanager. Because Hughes Aircraft at the time had a number of critical defense contracts, the 'disruption' in the corporate management (referred to internally as the Revolt at Culver City) alarmed the Secretary of the Air Force, who essentially gave Hughes an ultimatum that either he remove himself from the any personal role in the management of the company (of which he had made, according to the Secretary, "a hell of a mess") or he would cancel all Air Force contracts with Hughes Aircraft.

Hughes turned over the electronics portion of Hughes Aircraft to the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and in 1954 Pat Hyland took over control of Hughes Aircraft as Vice-President and General Manager. Under Hyland's direction, Hughes Aircraft became a leader in avionics, developing radar, guided missiles and missile and weapons guidance systems, the synchronous orbit communications satellite, and the Surveyor Lunar aircraft. When Hughes died in 1976, Hyland became the company's president and CEO.

In 1985 Hughes Aircraft was sold to General Motors and became GM-Hughes Electronics Corporation, a wholly owned subsidiary of General Motors. During the 1980s and '90s Hughes Electronics pioneered in telecommunications and satellite and network systems. In 1994 Hughes launched DirectTV in Jacksonville, Mississippi, and in 1995 DirectTV went global

In the late 90s the various Hughes companies had gone through realignments, reorganizations, mergers and spin-offs. Space and Communications were sold to Boeing, Hughes Helicopter to McDonnell-Douglas, and Delco Electronics to General Motors Delphi Automotive. The Summa Corporation, a holding company formed in 1972 to manage Hughes remaining investments, now primarily developed and managed Hughes's enormous real estate holdings on the west side of the Las Vegas valley. Hughes Electronics concentrated on consumer satellite service, DirectTV, DirectPC, and Spaceway, a broadband satellite system.

The Archives of Hughes Electronics Corporation contain the files and publications of the corporate communications department and include complete files of its corporate newsletters Hughes News, 1948-95, and Hughes Herald, 1996-7; press releases, 1956-96; Annual Reports; technical, informational and marketing publications; videos; corporate speeches; biographical files of executives; historical bio files; and photographs of Howard Hughes and aircraft (particularly the 'Spruce Goose'), developed by Hughes Aircraft and test flown by Howard Hughes.

The collection comprises approximately 125 cubic feet of material including large framed portraits of Hughes and corporate presidents. This collection provides unique and comprehensive internal documentation of one of the United States' most influential engineering firms for almost a half-century and for the whole period of its independent existence. As such it was the center of Hughes's corporate empire, and the company with the greatest and most long term impact in engineering, where Hughes's genius in fact lay. The Hughes engineering companies developed aircraft, helicopters, electronics and communications equipment and networks that still hold primary place in American industrial and commercial engineering. It also forms a significant historical record of the legacy of American icon, Howard Hughes.

Unrest in Culver City

(1) His importance in the hush-hush field of guided missiles is so great that the Secretary of the Air Force flies to his side when troubles arise. (2) ...rumor goes ...the Secretary... would love to have him out of the field entirely.

(1) This sentence is too exaggerated. It should be that the Sec'y of the Air Force came to California to see him when there was some rumor of unrest in his plant.

(2) Should be deleted. That is bad. I don't want him to have anything he can use against me. They have Fortune and Life on their side - and they are trying for Time. Anything you say here to support his cause is going to be damaging to me. It is my contention that nobody in the Air Force has anything but praise for the plant except him.

In His Own Words

One of the most intriguing files in the Hughes collections concerns a three-part series Look magazine published about Hughes in 1954. This particular series, one of the earliest extended bios of Hughes to appear in the popular media, was different from the countless other magazine articles that appeared or would appear about Hughes in that Howard Hughes himself agreed to meet with the writer, Stephen White, an associate editor of Look magazine. Hughes had met with and sometimes talked at length to reporters, but usually in the context of a particular event such as his around-the-world flight or the Senate Hearings in 1947, but he seldom commented on his own life. Look agreed that Hughes could read drafts of the story and have the opportunity to suggest changes or revisions and to correct factual inaccuracies.

Hughes did meet with Stephen White on at least two occasions during which Hughes offered detailed page by page comments. In the effort to assure that the corrections were made as stipulated by Hughes, a complete verbatim transcript was produced of the meetings, so that what was preserved is not simply an annotated manuscript or list of suggested changes, but a transcript of a conversation between Hughes and the writer in which Hughes discusses and elaborates on various aspects of this life and career, in his own words. It is the closest we have of an off-the-record interview, with Hughes commenting upon and reacting to many of the stories, rumors and legends that had already grown up around him by 1954. By this date Hughes had already withdrawn from the public eye, but not to the extent he would later when he allowed no contact with the media at all. This transcript is a curious document of Howard Hughes talking about Howard Hughes, before Howard Hughes withdrew completely into secrecy behind his army of agents and assistants. Hughes in this conversation was at times remarkably candid about some of the events of his life, at the same time displaying a growing obsession with protecting his reputation in aviation. Some of his quotes and comments made their way into the published article but many did not. What follows are excepts from these transcripts.

The Beginings

Hughes: My only comment here is Howard Hughes came in contact with speed at an early age and then if you could strike out 'that even today he drives a Chevrolet substantially faster than the law of common sense would call advisable'...

...Good grades at Fessenden and was an outstanding student at Thatcher but I was not goaded by my father and this had nothing to do with my learning to fly. The first opportunity I had to come in contact with the operation of an aircraft was at New London, Connecticut. We were at that time staying at the Griswold Hotel on the Thames River and we attended the Yale-Harvard boat races. My father had been on one of the crews at Harvard. I doubt that it was the Varsity Crew but he had some interest in rowing at Harvard and he was ardently anxious that Harvard win the race and promised me anything I wanted if Harvard should win. This was back in the old days when Harvard used the short stroke and Yale the long stroke. I remember that very well. We sat in the train and watched the race. My father thought I was going to ask for a canoe with a sail on it which I had been badgering him all summer to buy for me, but instead when Harvard won and he was ready to pay off his obligation to me I asked to be permitted to fly with a pilot who had an old broken down seaplane anchored in the river in front of the hotel and my father begrudgingly consented. He didn't like he looks of the contraption, corroded wires and so forth and so on but he finally gave in and this was the very first contact I had with flying...The age is correct -- 14.

White: Had your father done any flying?

Hughes: No. None at all. He was an ardent automobile driver but to my knowledge had never been up in an airplane.

I remember the airplane very well. It was a Curtis Flying Boat - not a land plane on pontoons. It was a single hull flying boat and the engine was overhead. It was a by-plane, and I'm quite sure it was a pusher. I think the engine was ahead of the propeller. If I remember right it was an OX5V-8 engine...

Father, high living and extravagant...anything but an efficient manager.

Hughes: The men in Houston worship him - why not say "his father, though a brilliant inventor, was prone to be extravagant." I wouldn't like anything about his management.

- He owns a factory that pours money into his pocket. . . .

- He hasn't seen the factory for 15 years and

- he runs it by telephone...

Hughes: (1) That isn't true - it makes some money but that goes into the Aircraft, etc. It doesn't pour into my pocket (2) This isn't true either - it hasn't been 15 years

White: Well, how long has it been?

Hughes: I don't know exactly - but more like 18 months. And on (3) that would be very much resented by the people down there.

White: OK I'll fix it.

Howard Hughes Aviator

Hughes: "It says the plane with which he set the land speed record was, as the fact indicates, the fastest plane built up to that time is not correct because there had been one or two seaplanes built for the Schneider Trophy Race which were faster. However they had practically no range and were only usable on a very very smooth lake with fuel enough for a few minutes flight, utterly impractical. This airplane [H-1 Racer] which is under discussion here was the fastest land plane which had ever been built and was the most efficient airplane ever built up to that time by a considerable amount... You see this airplane was fast because it was clean and yet it attained its speed with a Pratt and Whitney engine of perfectly normal design with normal reliability.

Now this follows - Hughes submitted a pursuit plane version of his design to the Army Air Corps and felt confident that after his demonstration of his trans-continental flight the army would be interested because this airplane was definitely faster than any military aircraft anywhere in the world - pursuit plane, bomber, or anything else... However the Army Air Corps did not accept this design. Right here I don't know exactly what reason to give. I don't want to indict the Army Air Corps for passing up the airplane so a little thought should be given to this. I have my own ideas as to why they didn't accept it but after all I'm doing a lot of business now with the Air Force and let's not generate any ill-will here.

Now regarding the Japanese Zero... The Japanese Zero was a shock of the utmost magnitude to the United States because it had been thought up to that time that the Japanese were far inferior mechanically, I should say in point of aircraft design and mechanical aptitude, to the United States and nobody expected the Japanese to have an airplane that would be at all competitive. Well, in any event, when one of these Japanese Zeros was finally captured and studied and analyzed it was quite apparent to everyone that it had been copied from the Hughes plane which has been discussed earlier here. That is the only relationship between the Japanese Zero and the Hughes H-I design. I had no dealings with the Japanese or any other foreign government for the plane and to the best of everyone's knowledge the Japanese had no other access to it except through whatever espionage they may have had or through seeing photographs of it which naturally were published all over the world.

Bill Utley: (attending the meeting as the Hughes company publicist, recounts how before the war a delegation of Japanese air force generals had seen the H-1 in a hangar in New Jersey) "They were late for a banquet in New York where they were being toasted and they saw your airplane and I have been told by Al Ludwick I think, that they couldn't drag them away from it, that they climbed all over it, that they examined it from head to toe, and that was the start of their interest in your airplane"

Hughes: Oh, really?

Utley: Yeah.

Hughes: Well, I don't think we better bring that in because there might be some question as to why the hell they were let in the hangar.

Utley: They had been invited here by the United States Government

Hughes: I know, but you can't explain all those things without going into too much detail

...There were photographs all over the place and I don't think the Japanese would have to see it to copy it - they could copy it from the pictures.

Around the World Flight, 1938

Hughes: I did not design the first automatic pilot by a long way so that is not correct

And I wouldn't say the first integrated radio navigation system or the first inclusive instrument panel... I think you can say that the radio equipment - which I did not design personally but was designed under my supervision, while my round the world flight was the first, well, I don't think you could even say first - I should say it was the best long-range radio communication system ever designed for an airplane and the entire navigation system both radio and celestial was certainly by far the most efficient ever installed or used up to that time and the navigation carried out on the flight was by far the most accurate of that performed in any long distance flight up to that time. The navigation throughout that flight around the world was so accurate that the plane was never more than a few miles off of the desired course

Utley: It was six miles

Hughes: It was amazingly accurate, and the combination radio and celestial equipment and dead reckoning systems and the entire system and procedure of navigation was amazingly effective and efficient but I don't think it's right to say it was actually the first of anything on here...

TWA and the Constellation

Hughes: In other words, up to the time of the Hudson bomber Lockheed really had not achieved any success of consequence. It is interesting to note that the three airplanes which accounted for Lockheed's success up until the end of World War II were the Hudson Bomber, which might never have become a reality without Hughes flight around the world; the P-38, which in some manner had its origin from the Hughes conceived 2-engine interceptor that Hughes-submitted to the Air force; and thirdly, the Constellation, which Hughes requested Lockheed to build. I'm sure the story on the Constellation is covered elsewhere but, in short, Hughes took the preliminary design to Consolidated and Rube Fleet refused it, and then Hughes took it into Lockheed, and Lockheed finally agreed to build it with Hughes taking all the financial risks.

Now this part of the story, however, and everything to do with Lockheed should be handled with some consideration not to peak (sic) the pride of Lockheed too much. In other words, naturally, if you give the Hughes version of this thing they are not going to be very happy about it and, naturally, their story would be somewhat different but I think the facts sustain what I have just said. Of course I probably haven't given myself any of the worst of it.

Jack Frye, President of TWA when it was acquired by Hughes, did in fact have a somewhat different story which he provided in a letter to the editor of Look magazine.

"As a reader of Look, I have noted with personal interest the references made to me and TWA in your current series of articles - The Howard Hughes Story.

A number of my friends in the aviation field have called my attention to, and I have recognized as much myself, several gross errors appearing in the article which refers to Mr. Hughes's introduction to TWA and that part concerning me...

The references concerning that part Mr. Hughes performed in connection with the Boeing Stratoliner and Constellation are grossly exaggerated . . . TWA had already secured bids from one manufacturer on the airplane in question that ultimately evolved into the Constellation - before Mr. Hughes ever showed interest in TWA or became its principal stockholder.

In conclusion, I would like to say that Mr. Hughes deserves credit for having the courage to financially support the purchase of the Stratoliner and Constellation after he purchased a stock interest in TWA."

XF-11 The Plane that Nearly Killed Him

Hughes: I don't like this page at all. I think this page is misleading. I suggest that in place of the first sentence you say something like the following:

With respect to all the airplanes which Hughes had designed and built - going clear back to his very first airplane, the H-1 - he had followed a rigid policy of making the flying tests himself. When questioned about this he always said, "If I have made a mistake in the design, then I'm the one who should pay for it, and I certainly would not ask somebody else to fly the plane if I were afraid to do it myself."

When we move into the second sentence on page 210, I want to suggest that we delete what we have here completely, and that a scrutiny be made of my testimony with respect to this incident, which was made before the Air Force Board of Inquiry. We have this somewhere. Miss Henley can probably dig it out. I'm not talking about the Senate testimony. In other words, I say that you should dig out my testimony which I made before the Board of Inquiry down here in Los Angeles.

I notice here that in the later pages you have cited the Air Force conclusion that it was pilot error, etc. I read the conclusion of this Board of Inquiry very carefully, and I don't think it was quite what we have summarized here. Secondly, I think that it was a very partial and unfair conclusion, which I protested at the time.

I don't say that my version and testimony should prevail over the conclusion of this Board. But, likewise, I don't think it fair to say that this was an impartial board; there were very strong indications that this Board did not make a careful study of the accident. There was a great deal of evidence which was not available at the time this conclusion was reached. In fact, the Board if Inquiry was composed of a group of young officers who were jealous, in the first place. Secondly, as I say, they didn't have the facts. There was a strong doubt in the minds of the officers on this Board as to whether there had really, in fact, been a malfunctioning of the propeller. Their entire conclusion, as I say, was one which I feel was loaded with partiality, and I think that one factor influencing this report of this Board of Inquiry was that the government had an enormous amount of money in this super hydromatic propeller which was on this airplane. And the Air Force certainly did not want to see the establishment of any proof that this propeller actually was a failure or malfunctioned.

Now I feel there is no question but what had an impartial Board of Inquiry met on this matter after it was thoroughly proven that this propeller was, in truth, defective, that then the result would have been quite different. Because the theory, that I should have known that this dissymmetry in the airplane's flight tendencies and attitude was caused by the propeller, and by some other structural failure. That theory is a very, very thin one, because with a dual rotation propeller and only half of the propeller in reverse - not all of it - it was very obvious that all instruments indicated the power plant and the propeller to be functioning normally. And I just don't think that a more thorough scrutiny of this matter would lead anyone to the conclusion that the pilot had any rhyme or reason or opportunity to believe that the trouble was caused by the propeller.

And I think, Steve, if you want to give this fair treatment you ought to consider my testimony as being pretty damned accurate, because I was the only one there; and I think later evidence pretty well showed that it was accurate, otherwise I'm sure the Air Force never would have permitted me to fly the second F-11.

Just a couple of points here to illustrate what I feel we're off the beam a little bit. You say, "He was trying to peer at the plane's under carriage when he lost control entirely." Hell, there was no loss of control. The airplane was completely under control right up to the time it hit the house. There never was a semblance of any stall or spin or anything of that kind at all. It was just a matter of a steady loss of altitude, due to the fact that this right propeller was in reverse, and the extreme throw of the controls, both the aileron and the rudder, was necessary to keep the plane from falling into a spin to the right. But there was never any slightest tendency - I wouldn't say tendency; naturally it wanted to all the time, but there was never any slightest indication that the airplane was out of control at any time. I mean its flight path and the way it contacted the houses, and the entire, well, all the facts involved, and the reports of all observers, and my report all confirmed that the airplane at no time went out of control.

Incidentally, later scrutiny of the X-Rays showed that I broke 24 ribs; every single rib, not eleven.

Stephen White deleted the story of the flight and crash of the XF-11 in the final article

Flying Again After the crash

It was very important to Hughes to prove that he could still fly after his near fatal crash, for his own personal image of the daring aviator who had walked away from crashes, but also to dispel any doubts about his competence as a pilot. This flight was heavily publicized by Hughes PR people. The photos of Hughes show him haggard and drawn in his triumph. It was the severity of his injuries that occasioned his use of the pain-killers to which he became addicted.

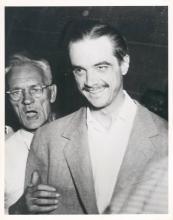

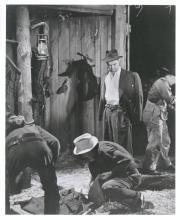

Senate Hearings, 1947

Hughes preparing to testify before Senate War Investigating Committee, August 6, 1947. Despite his company's poor performance on government contracts during the war and some questionable methods in obtaining those contracts, Hughes emerged from the hearings and in public opinion as a persecuted aviation hero, who bested the bumbling Republican-dominated committee bent on discrediting the Roosevelt administration and on protecting the transcontinental monopoly of Pan Am from Hughes's TWA. Prior to his appearance, Hughes launched a vitriolic media campaign against the Committee and in particular against Senator Ralph Brewster through the Hearst newspapers.

Hughes: I suggest that you substitute for the entire page 227:

"In due time Hughes flew in from the West Coast, piloting his own plane, and disembarked at Washington with a minimum of toilet articles and one clean suit thrown over his shoulders. Having elaborately made reservations at the Mayflower Hotel, he proceeded at once to the Carlton Hotel, where he had hopes of finding a room which had not been equipped with a microphone. (His rooms at the Carlton, however, were later tapped by lowering a microphone down through a ventilating duct. The report is that all anyone ever monitored from these rooms was a phrase in which Hughes described Brewster in terms utterly unrepeatable in public - or in most private groups, for that matter.)"

The Flying Boat, a.k.a. the Spruce Goose

Hughes: These three pages... I feel do not give a clear or fair picture of the overall subject being covered here. In other words, if you found these quotes in my testimony [the 1947 Senate Hearings] then undoubtedly I testified in this manner, but this was a small part of a great deal of testimony and I think that here we have singled out a very weak portion of my testimony and used it to rebut some very strong statements by the opposition.

In other words my summary of this would be as follows: From the outset - now this is what I would call a fair statement in lieu of and in substitution for pages 200, 202 and 202 - From the outset the Army and the Air Corps and the Navy were opposed to this project because it had not originated through normal Army or Navy or Air Corps channels. It had originated through an appeal to the public made by Henry Kaiser. The Army, Navy, and Air Corps did not like projects to originate in this way...

The services liked to participate in the design of their product and I'm not going into argue the merit or demerit of this particular policy.

...now getting back to the Flying Boat. In this particular situation the Services were even more opposed to this project than they would have been had Douglas or Boeing, for example, designed and built an airplane on speculation without Air force participation. The Services were violently opposed to this airplane because they felt it had been pushed through by political pressure. It was not wanted by the Services. The Services considered it, in truth, a sort of slap or insult to their own efficiency up to that time. In other words this project was pushed through by Henry Kaiser on the basis that there was a crying need for it and why hadn't somebody built some cargo planes up to that time.

In other words, this thing was a black sheep. Nobody wanted to fool around with it or become contaminated by it and that probably accounts for the meager information. I don't believe anybody harried me for any reports to reveal progress or any of the rest of that. I just don't believe that occurred.

Now, I say, up to that time this airplane, and I think you will find this in my testimony, represented a lesser cost per pound to the taxpayers and a quicker delivery per pound than any... and consequently I think this represented a very, very cheap and very quick job.

Now in this particular airplane, however, the increase in size beyond the largest airplane ever designed or built prior thereto, was 3 times. In other words, I think this airplane was roughly 3 times larger than the largest airplane that had ever been built or designed thereto. Now this made such an enormous increment of increase that it carried us beyond the point on any available curves of known design criteria - beyond the point where extrapolation was possible. In other words, we were just way off the end of the paper and there was no way to take existing design information, design criteria, and extrapolate the curves a little ways beyond and say this is what ought to happen if it is this much bigger than the one before. This airplane was so much bigger than the one before, than anything that anybody had ever conceived up to that time, that we were working in a complete vacuum as to information based upon prior performance and prior design.

Now, furthermore, I may say that this airplane for the very first time in history reached into a size where manual control was utterly impossible, and this was just as important a barrier to cross as crossing the sonic barrier in speed.

Now in the case of this aircraft, the Hughes flying boat, the controls were so large, so much larger than any designed before, that for the first time we crossed into the area wherein it is absolutely impossible for any human being, whether he be Jack Dempsey or Joe Lewis rolled into one, it's utterly impossible for any human being to move the controls of this airplane - consequently it became necessary for the first time to design power control system which was as safe, let's say, as the structure of the airplane

So, although I may have admitted here that we could have done the airplane faster had we been less cautious and less careful in some respects, this was not intended to acknowledge that in any way the design or the manufacture of this airplane by standards of cost or time was in any way inferior to what it should have been. In fact, I say again, the facts show that it was a damn sight better than anyone could have expected.

Needless to say, I implore that this be deleted in its entirety. This would be an extremely unfair statement to make. The design of this airplane is not obsolete in any way. As a matter of fact, it is still way ahead of the power plants available... The design is not obsolete; in fact I defy anyone today to design an airplane substantially more efficient than this one for its purpose; namely the economical hauling of large heavy pieces of military equipment, such as tanks, field guns, artillery pieces, etc., over long distances.

Hughes in Hollywood

Howard Hughes receiving congratulations from the California and Hollywood American Legion Post Commanders, 1952, for his highly (self) publicized "war on Hollywood communists." Hughes fired screenwriter Paul Jarrico who had written the screenplay for RKO's forgettable Meet Me in Las Vegas (another vehicle for Jane Russell) after Jarrico was subpoenaed to testify before the House Un-American Activities Commitee. After Jarrico refused to answer the Committee's questions, Hughes had his name removed from the film's credits, which was protested by Jarrico and the Screen Writer's Guild. Hughes answered characteristically with a lawsuit claiming that Jarrico had, by refusing to testify, violated the standard morals clause in his contract with RKO. Although Hughes was acclaimed as a hero by the anti-communists of the day, the incident left Hughes in a bad odor in Hollywood.

Air combat scene from "Hells Angels" (pictured above). The movie was originally shot as a silent movie. The sound and the ingénue starlet Jean Harlowe were added later.

(1) ...The studio has lost a fortune since he took it over, (2) it makes virtually no pictures at all

Hughes: (2) is pretty rough. We made enough pictures to carry our distribution set up.

White: I think you made the magnificent sum of 5 pictures in one year but I can't remember which year it was.

Hughes: I suppose you didn't count the independent productions. Those should be considered part of the total.

White: Even if you count independent productions - it is far less than was planned at the beginning of the year.

Hughes: The number of releases planned is exaggerated for exhibitors - you know that. Can't you say something to the effect, "However, since taking over RKO the studio has lost money?"

White: I'll compromise with you.

Hughes: I object to "fortune" and "virtually no pictures."

Hated by a large majority of the film colony

Hughes: I think "large majority" is going a little far. I think it is true that you could say "by a substantial number of the film colony."

Gina Lollabrigida and Ursula Theis

Hughes: I think this is very harmful, I wish you would see your way clear to change it. I want to have further discussion with you on this later. I never went out with Ursula Theis in my life, and we may wind up in a lawsuit with Lollobrigida with regard to her contract, so let's not make her madder than she is. Anyway she wouldn't be saying those kind things about me.

White: I will take out Theis and Lollabigida entirely.

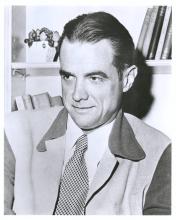

Hughes Portraits

Noah Dietrich, Hughes's long-time friend and business manager, whom Hughes fired in a pique of paranoia in 1957, commented later that a reason for Hughes's intense reclusiveness was his fear of people seeing what he looked like. Hughes was a strikingly handsome man in his early years - he had an almost Hollywood movie star face. After his near fatal crash in 1947, the Senate Hearings, and test flight of the Flying Boat, Hughes looked much older, almost haunted. Like many aging celebrities Hughes preferred flattering photos which were often re-touched.

One of the curious mysteries of his portraits and his appearance in general was his mustache, about which he seemed unable to decide. He was clean shaven in his early years, and he sported a mustache later, but in his official photos the mustache was on and off, in the PR files there were copies of the same portrait, one with, one without mustache. There were of course no known or at least acknowledged or official photos of Hughes after the mid-1950s, although he did not withdraw completely from public until the later '60s. There were various artist speculation of Hughes as an old man, with long hair and a beard, but his appearance became part of the myth and mystery of Howard Hughes.

Project Credits

Collection Development

This collection features photographic images and portraits documenting Howard Hughes. There are 94 images selected from two collections: The Howard Hughes Collection and the Hughes Electronics Collection. All collections are housed at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas in the Special Collections at the University Libraries.

Digitization

Welcome Home, Howard!: or Whatever Became of the Daring Aviator? began as a web exhibit created by Special Collections to showcase its Howard Hughes collections in the wake of the publicity surrounding Martin Scorsese’s 2004 biopic about Howard Hughes, The Aviator. The photographs and documents were selected, and the contextual narrative written by Peter Michel, Director of Special Collections. The Libraries digitization staff scanned the photographic prints using either Canon CanoScan 9950 scanners or the Epson XL10000 with Easy Scan 7.1 software. The high-resolution (300 dpi, 24-bit) TIFF files are archived in the Web and Digitization unit of the Libraries.

The collection was converted into a searchable collection in 2008 and is presented using OCLC's CONTENTdm software. Dublin Core metadata was created for each item and entered into the database. To increase successful resource discovery, research was done by indexers and a variety of access points were included in the project metadata: date, subject, geographic location, and selected aircraft are examples of collection search terms that use controlled vocabulary. This vocabulary is created locally and/or derived from the Library of Congress' Thesaurus for Graphic Materials I: Subject Terms, the Getty Thesaurus for Geographic Names and The Library of Congress Name Authority File. Peter Michel provided the narrative structure for the website and contributed all text and scholarly content for the each of the chapter in the project.

Acknowledgements

Collection Development: Peter Michel, Director of Special Collections

Metadata Consultant: Kathy Rankin, Special Collections Cataloger

Project Team

Cory Lampert, Digitization Projects Librarian

Annie Sattler, Digitization Assistant/Metadata Specialist

Brian Egan, Web/Multimedia Designer

Alex Dolski, Web and Digitization Application Developer

John Fox, Information Systems Specialist

Michael Yunkin, Web Content/Usability Specialist

Copyright

Not to be reproduced without permission. To purchase copies of images and/or for copyright information, contact University of Nevada, Las Vegas Libraries, Special Collections. Welcome Home Howard! is published by University of Nevada Las Vegas, University Libraries, October 2008.

Contact

For additional information about the content contained in Welcome Home Howard, including reproductions, permissions, and access to related collections, contact Peter Michel. For questions about this digital collection and the digitization project methods, please contact Cory Lampert. General comments, corrections, and feedback are always welcome.

E-mail: wds@unlv.edu

Phone: (702) 895-2209

Mailing Address:

University of Nevada, Las Vegas Libraries

Mail Stop 7010

4505 S. Maryland Parkway

Las Vegas, NV 89154-7010

U.S.A.