Copyright & Fair-use Agreement

UNLV Special Collections provides copies of materials to facilitate private study, scholarship, or research. Material not in the public domain may be used according to fair use of copyrighted materials as defined by copyright law. Please cite us.

Please note that UNLV may not own the copyright to these materials and cannot provide permission to publish or distribute materials when UNLV is not the copyright holder. The user is solely responsible for determining the copyright status of materials and obtaining permission to use material from the copyright holder and for determining whether any permissions relating to any other rights are necessary for the intended use, and for obtaining all required permissions beyond that allowed by fair use.

Read more about our reproduction and use policy.

I agree.Information

Digital ID

Permalink

Details

Member of

More Info

Rights

Digital Provenance

Publisher

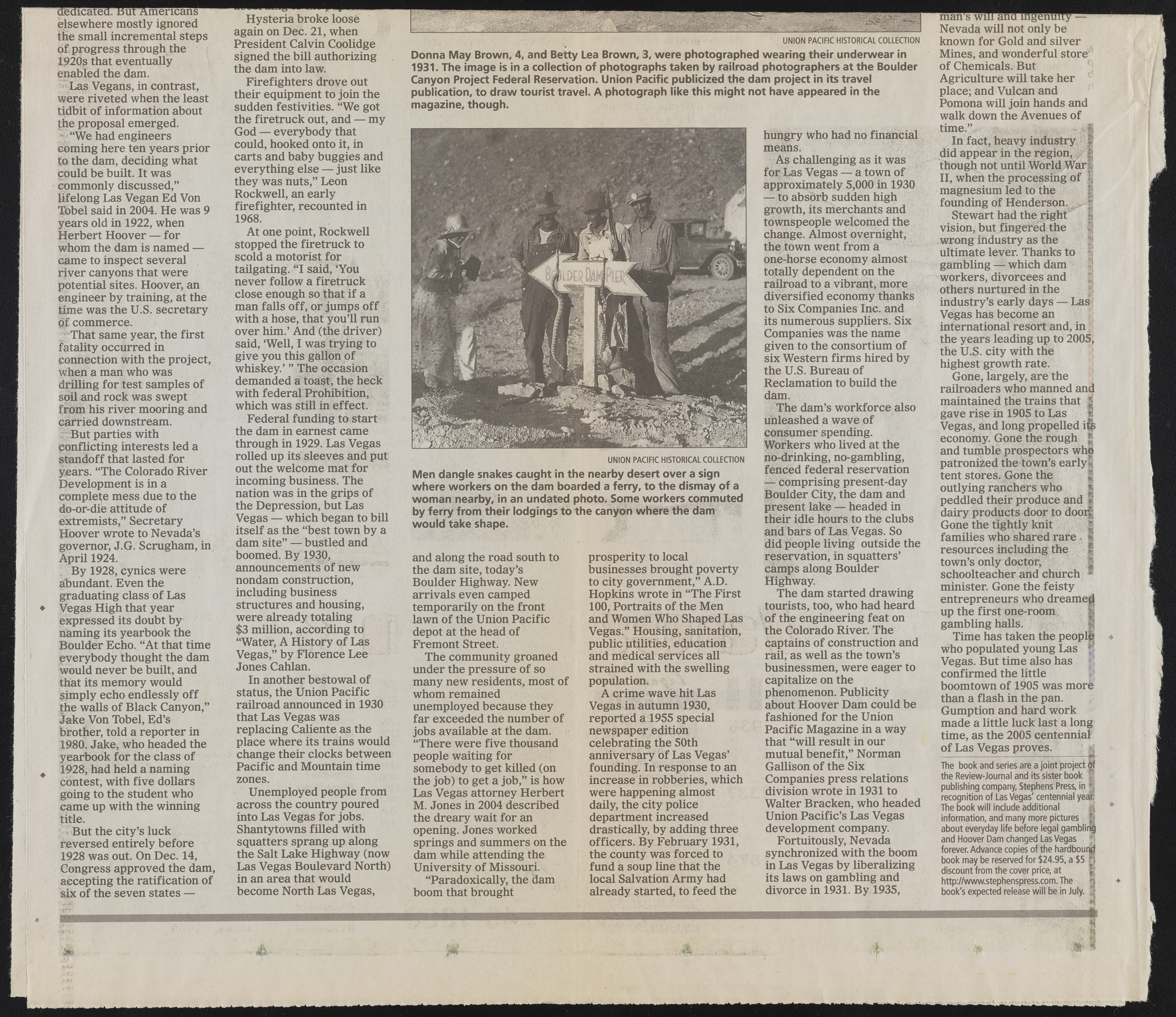

Transcription

lecucatea. tsur Americans-elsew here mostly ignored tiie small incremental steps o f progress through the 1920s that eventually enabled the dam. * La$ Vegans, in contrast, were riveted when the least tidbit of information about {he proposal emerged. “We had engineers coming here ten years prior to the dam, deciding what could be built. It was commonly discussed,” lifelong Las Vegan Ed Von Tobel said in 2004. He was 9 years old in 1922, when fferbert Hoover — for whom the dam is named — came to inspect several \ river canyons that were potential sites. Hoover, an engineer by training, at the time was the U.S. secretary flf commerce. H That same year, the first fatality occurred in connection with the project, whep a man who was drilling for test sam ples of soil and rock was swept from his river mooring and carried downstream. ::B ut parties with Conflicting interests led a standoff that lasted for years. “The Colorado River Development is in a com plete m ess due to the do-or-die attitude of extrem ists,” Secretary Hoover wrote to Nevada’s governor, J.G. Scrugham, in April 1924. | | By 1928, cynics were Abundant. Even the graduating class of Las ? Vegas High that year expressed its doubt by naming its yearbook the Boulder Echo. “At that tim e everybody thought the dam would never be built, and that its memory would 3jmply echo endlessly off the walls of Black Canyon,” Jake Von Tobel, Ed’s brother, told a reporter in 1980, Jake, who headed the yearbook for the class of fe 1928, had held a naming contest, with five dollars going to the student who came up with the winning title. t But the city’s luck reversed entirely before 1928 was out. On Dec. 14, Congress approved the dam, accepting the ratification of ^ix of the seven states — H ysteria broke loose again on Dec. 21, when President Calvin Coolidge signed the bill authorizing the dam into law. Firefighters drove out their equipment to join the sudden festivities. “We got the f iretruck out, and — my God — everybody that could, hooked onto it, in carts and baby buggies and everything else — just like they was nuts,” Leon Rockwell, an early firefighter, recounted in 1968. At one point, Rockwell stopped the firetruck to scold a motorist for tailgating. “I said, ‘You never follow a firetruck close enough so that if a man falls off, or jumps o ff with a hose, that you’ll run over him.’ And (the driver) said, ‘Well, I was trying to give you this gallon of whiskey.’ ’’ The occasion demanded a toast, the heck with federal Prohibition, which was still in effect. Federal funding to start the dam in earnest came through in 1929. Las Vegas rolled up its sleeves and put out the welcome mat for incoming business. The nation was in the grips of the Depression, but Las Vegas — which began to bill itself as the “best town by a dam site”— bustled and boomed. By 1930, announcements of new nondam construction, including business structures and housing, were already totaling $3 million, according to “Water, A History of Las Vegas,” by Florence Lee Jones Cahlan. In another bestowal of status, the Union Pacific railroad announced in 1930 that Las Vegas was replacing Caliente as the place where its trains would change their clocks between Pacific and Mountain time zones. Unemployed people from across the country poured into Las Vegas for jobs. Shantytowns filled with squatters sprang up along the Salt Lake Highway (now Las Vegas Boulevard North) in an area that would become North Las Vegas, UNION PACIFIC HISTORICAL COLLECTION ffiSL a t ^ - ^ i i ''V mm UNION PACIFIC HISTORICAL COLLECTION Donna M ay Brown, 4, and Betty Lea Brown, 3, w ere photographed wearing their underwear in 1931. The image is in a collection of photographs taken by railroad photographers at the Boulder Canyon Project Federal Reservation. Union Pacific publicized the dam project in its travel publication, to draw tourist travel. A photograph like this m ight not have appeared in the magazine, though. hungry who had no financial means. As challenging as it was for Las Vegas — a town of approximately 5,000 in 1930 — to absdrb sudden high growth, its merchants and townspeople welcomed the change. Almost overnight, the town went from a one-horse economy almost totally dependent on the railroad to a vibrant, more diversified economy thanks to Six Companies Inc./and its numerous suppliers. Six Companies was the name given to the consortium of six Western firm s hired by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation to build the dam. The dam’s workforce also urileashed a wave of consumer spending. Workers who lived at the no-drinking, no-gambling, fenced federal reservation ?4* comprising present-day Boulder City, the dam and present lake — beaded in their idle hours to the clubs and bars of Las Vegas. So did people living outside the reservation, in squatters’ camps along Boulder highway. The dam started drawing tourists, too, who had heard of the engineering feat on the Colorado River. The captains of construction and rail, as w ell as the town’s businessmen, were eager to capitalize on the phenomenon. Publicity about Hoover Dam could be fashioned for the Union Pacific Magazine in aw ay that “w ill result in our mutual benefit,” Norman Gallison of the Six Companies press relations division wrote in 1931 to Walter Bracken, who headed Union Pacific’s Las Vegas development company. Fortuitously, Nevada synchronized with the boom in Las Vegas by liberalizing its laws on gambling arid divorce in 1931. By 1935, Men dangle snakes caught in the nearby desert over a sign where workers on the dam boarded a ferry, to the dismay of a w om an nearby, in an undated photo. Some workers commuted by ferry from their lodgings to the canyon where the dam w ould take shape. and along the road south to the dam site, today’s Boulder Highway. New arrivals even camped temporarily on the front lawn of the Union Pacific depot at the head of Fremont Street. The community groaned under the pressure of so many new residents, most of whom remained unemployed because they far exceeded the number of jobs available at the dam. “There were five thousand people waiting for somebody to get killed (on the job) to get a job,” is how Las Vegas attorney Herbert M. Jones in 2004 described the dreary wait for an opening. Jones worked springs and summers on the dam while attending the University of Missouri. “Paradoxically, the flam boom that brought prosperity to local businesses brought poverty to city government,” A.D. Hopkins wrote in “The First 100, Portraits of the Men and Women Who Shaped Las Vegas.” Housing, sanitatfqh, public utilities, education and medical services all * strained with the swelling population. A crim e wave hit Las Vegas in autumn 1930, reported a 1955 special newspaper edition celebrating the 50th anniversary of Las Vegas’ founding. In response to an increase in robberies, which were happening almost daily, the city police department increased drastically, by adding three officers. By February 1931, the county was forced to fund a soup line that the local Salvation Army had already started, to feed the ?PPh man s win ana mgenuir Nevada w ill not only be known for Gold and silver Mines, and wonderful store"' of Chemicals. But Agriculture w ill take her place; and Vulcan and Pomona will join hands and walk down the Avenues of tim e.’V \ In fact, heavy industry 1 did appear in the region, v I though not until World W ari II, when the processingof I magnesium led to the founding of Henderson. I Stewart had the pghf* 1 vision, but fingered the f wrong industry as the ultimate lever. Thanks to | gambling which dam | workers, divorcees and 2 others nurtured in the industry’s early days — Las | Vegas has become an international resort and, in j! the years leading up to 20051 the U.S. city with tb$ highest growth rate. Gone, largely, are the railroaders who manned am| maintained the trains that § gave rise in 1905 to Las I Vegas, and long propelled i^ economy. Gone the rough | and tumble .prospectors w h | patronised the town’s earlyl tent stores. Gone the outlying ranchers who peddled their produce and 1 dairy products door to dooifjjj Gone the tightly knit fam ilies who shared rare, 1 resources including the 1 town’s only doctor, schoolteacher and church * minister. Gone the feisty entrepreneurs who dreamej| up the first one-room gambling halls. Time has taken the peopli who populated young Las § Vegas. But tim e also has j confirmed the little boomtown of 1905 was morC than a flash in the pan. Gumption and hard work made a little luck last a long time, as the 2005 centennial of Las Vegas proves. The book and series are a join t project w the Review-Journal and its sister book I t publishing company, StephensiPress, ip j recognition o f Las Vegas' centennial y e ^ f The book w ill include additional information, and m any m ore pictures § § about everyday life before legal g a m b lirl and Hoover Dam changed Las Vegas § forever. Advance copies o f the hardbound book may be reserved fo r $24.95, a $5 p discount from the cover price, a t http://www.stephenspress.com. The 1 book's expected release w ill be in July. I? 3 ' ? 4| 1 -3-%