Copyright & Fair-use Agreement

UNLV Special Collections provides copies of materials to facilitate private study, scholarship, or research. Material not in the public domain may be used according to fair use of copyrighted materials as defined by copyright law. Please cite us.

Please note that UNLV may not own the copyright to these materials and cannot provide permission to publish or distribute materials when UNLV is not the copyright holder. The user is solely responsible for determining the copyright status of materials and obtaining permission to use material from the copyright holder and for determining whether any permissions relating to any other rights are necessary for the intended use, and for obtaining all required permissions beyond that allowed by fair use.

Read more about our reproduction and use policy.

I agree.Information

Digital ID

Permalink

Details

More Info

Rights

Digital Provenance

Publisher

Transcription

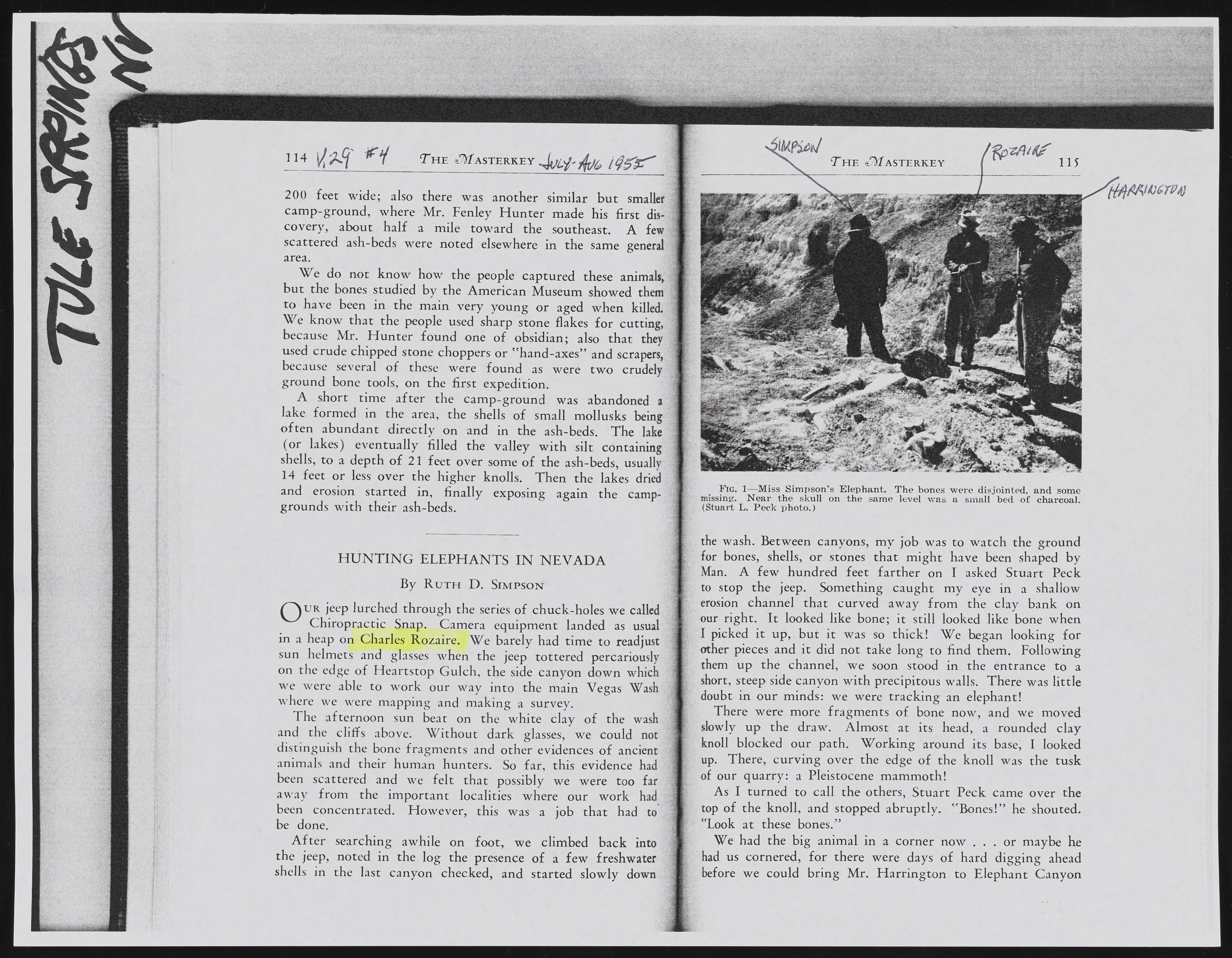

114 T h e a s t e r k e y ^ 200 feet wide; also there was another similar but smaller camp-ground, where Mr. Fenley Hunter made his first discovery, about half a mile toward the southeast. A few scattered ash-beds were noted elsewhere in the same general area.W e do not know how the people captured these animals, but the bones studied by the American Museum showed them to have been in the main very young or aged when killed. We know that the people used sharp stone flakes for cutting, because Mr. Hunter found one of obsidian; also that they used crude chipped stone choppers or "hand-axes” and scrapers, because several of these were found as were two crudely ground bone tools, on the first expedition. A short time after the camp-ground was abandoned a I lake formed in the area, the shells of small mollusks being | often abundant directly on and in the ash-beds. The lake jf (or lakes) eventually" filled the valley with silt containing shells, to a depth of 21 feet over some of the ash-beds, usually 14 feet or less over the higher knolls. Then the lakes dried and erosion started in, finally exposing again the campgrounds with their ash-beds. HUNTING ELEPHANTS IN NEVADA By R u t h D. Si m p s o n jeep lurched through the series of chuck-holes we called Chiropractic Snap. Camera equipment landed as usual in a heap on Charles Rozaire. We barely had time to readjust sun helmets and glasses when the jeep tottered percariously on the edge of Heartstop Gulch, the side cany^on down which we were able to work our way into the main Vegas Wash where we were mapping and making a survey. The afternoon sun beat on the white clay of the wash and the cliffs above. Without dark glasses, we could not distinguish the bone fragments and other evidences of ancient animals and their human hunters. So far, this evidence had been scattered and we felt that possibly we were too far away from the important localities where our work had been concentrated. However, this was a job that had to be done. A fter searching awhile on foot, we climbed back into the jeep, noted in the log the presence of a few freshwater shells in the last canyon checked, and started slowly down t t f l W Fig. 1— Miss Simpson’s Elephant. The bones were disjointed, and some missing:. Near the skull on the same level was a small bed of charcoal. (Stuart L. Peck photo.) the wash. Between canyons, nry job was to watch the ground for bones, shells, or stones that might have been shaped by Man. A few hundred feet farther on I asked Stuart Peck to stop the jeep. Something caught my eye in a shallow erosion channel that curved away from the clay bank on our right. It looked like bone; it still looked like bone when I picked it up, but it was so thick! We began looking for other pieces and it did not take long to find them. Following them up the channel, we soon stood in the entrance to a short, steep side canyon with precipitous walls. There was little doubt in our minds: we were tracking an elephant! There were more fragments of bone now, and we moved slowdy up the draw. Almost at its head, a rounded clay knoll blocked our path. Working around its base, I looked up. There, curving over the edge of the knoll was the tusk of our quarry: a Pleistocene mammoth! As I turned to call the others, Stuart Peck came over the top of the knoll, and stopped abruptly. "Bones!” he shouted. "Look at these bones.” We had the big animal in a corner now . . . or maybe he had us cornered, for there were days of hard digging ahead before we could bring Mr. Harrington to Elephant Canyon