Copyright & Fair-use Agreement

UNLV Special Collections provides copies of materials to facilitate private study, scholarship, or research. Material not in the public domain may be used according to fair use of copyrighted materials as defined by copyright law. Please cite us.

Please note that UNLV may not own the copyright to these materials and cannot provide permission to publish or distribute materials when UNLV is not the copyright holder. The user is solely responsible for determining the copyright status of materials and obtaining permission to use material from the copyright holder and for determining whether any permissions relating to any other rights are necessary for the intended use, and for obtaining all required permissions beyond that allowed by fair use.

Read more about our reproduction and use policy.

I agree.Information

Digital ID

Permalink

Details

More Info

Rights

Digital Provenance

Publisher

Transcription

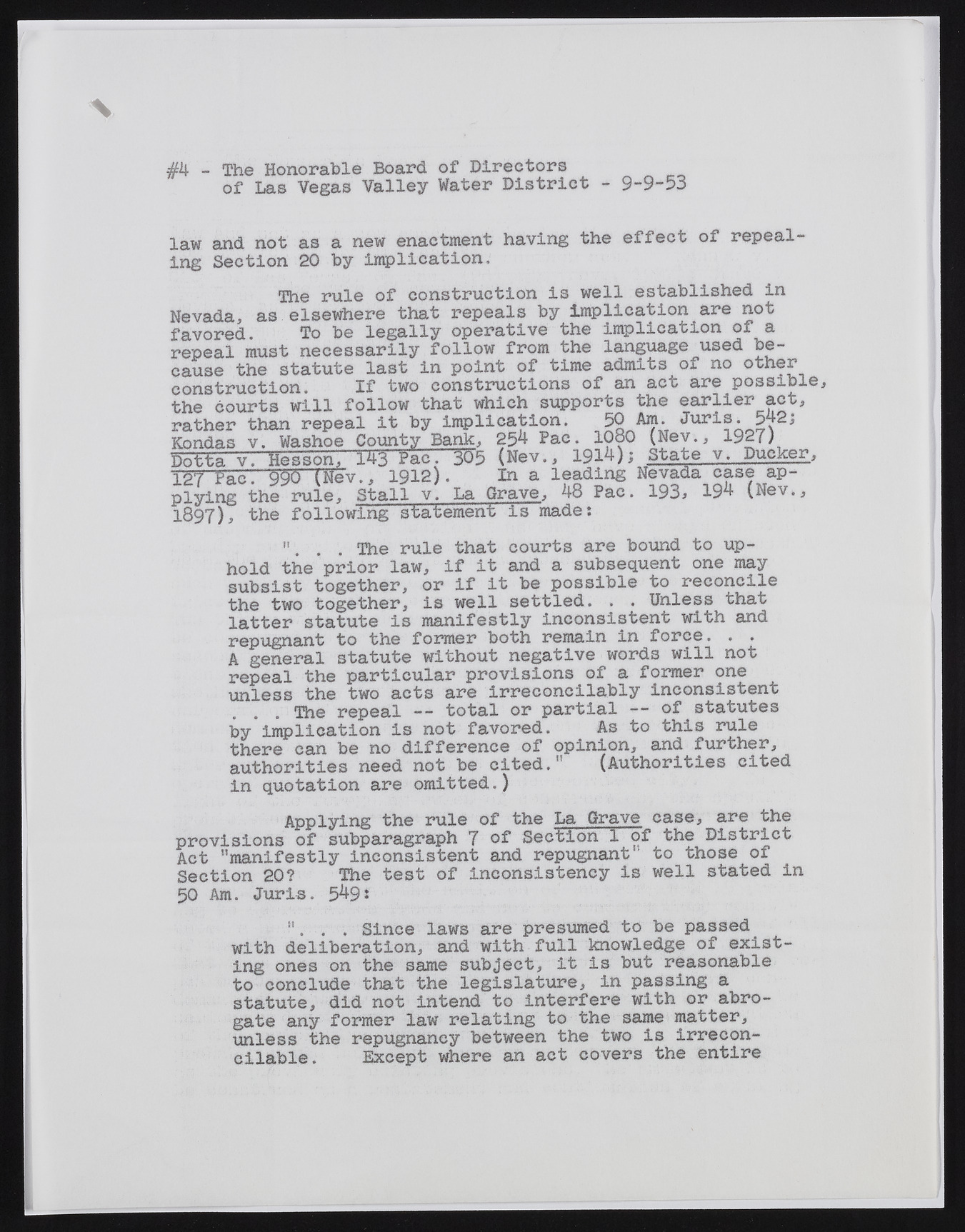

$4 - The Honorable Board of Directors of Las Vegas Valley Water District - 9-9-53 law and not as a new enactment having the effect of repeal ing Section 20 by implication. The rule of construction is well established in Nevada, as elsewhere that repeals by implication are not favored. To be legally operative the implication of a repeal must necessarily follow from the language used because the statute last in point of time admits of no other construction. If two constructions of an act are possible, the courts will follow that which supports the earlier act, rather than repeal it by implication. Juris. 542> Kondas v. Washoe County Bank, 254 Pac. 1080 (Nev., 1927} Dotta v. Hesson, 143 Pac.3^5 (Nev., 191^)J State v. Pucker, 127 Pac. '9^6.(lev., 1912). In a leading Nevada case ap- plying the rule, Stall v. La Grave, 48 Pac. 193> 194 (Nev., 1897), the following statement is made: "... The rule that courts are bound to uphold the prior law, if it and a subsequent one may subsist together, or if it be possible to reconcile the two together, is well settled. . . Unless that latter statute is manifestly Inconsistent with and repugnant to the former both remain in force. . A general statute without negative words will not repeal the particular provisions of a former one unless the two acts are irreconcilably Inconsistent . . . Hie repeal — total or partial — of statutes by implication is not favored. As to this rule there ean be no difference of opinion, and further, authorities need not be cited." (Authorities cited in quotation are omitted.) Applying the rule of the La Grave case, are the provisions of subparagraph 7 of Section 1 of the District Act "manifestly inconsistent and repugnant ‘ to those of Section 20? The test of inconsistency is well stated in 50 Am. Juris. 5^9• ". . . Since laws are presumed to be passed with deliberation, and with full knowledge of existing ones on the same subject, it is but reasonable to conclude that the legislature, in passing a statute, did not intend to interfere with or abrogate any former law relating to the same matter, unless the repugnancy between the two is irreconcilable. Except where an act covers the entire