Copyright & Fair-use Agreement

UNLV Special Collections provides copies of materials to facilitate private study, scholarship, or research. Material not in the public domain may be used according to fair use of copyrighted materials as defined by copyright law. Please cite us.

Please note that UNLV may not own the copyright to these materials and cannot provide permission to publish or distribute materials when UNLV is not the copyright holder. The user is solely responsible for determining the copyright status of materials and obtaining permission to use material from the copyright holder and for determining whether any permissions relating to any other rights are necessary for the intended use, and for obtaining all required permissions beyond that allowed by fair use.

Read more about our reproduction and use policy.

I agree.Information

Digital ID

Permalink

Details

More Info

Rights

Digital Provenance

Publisher

Transcription

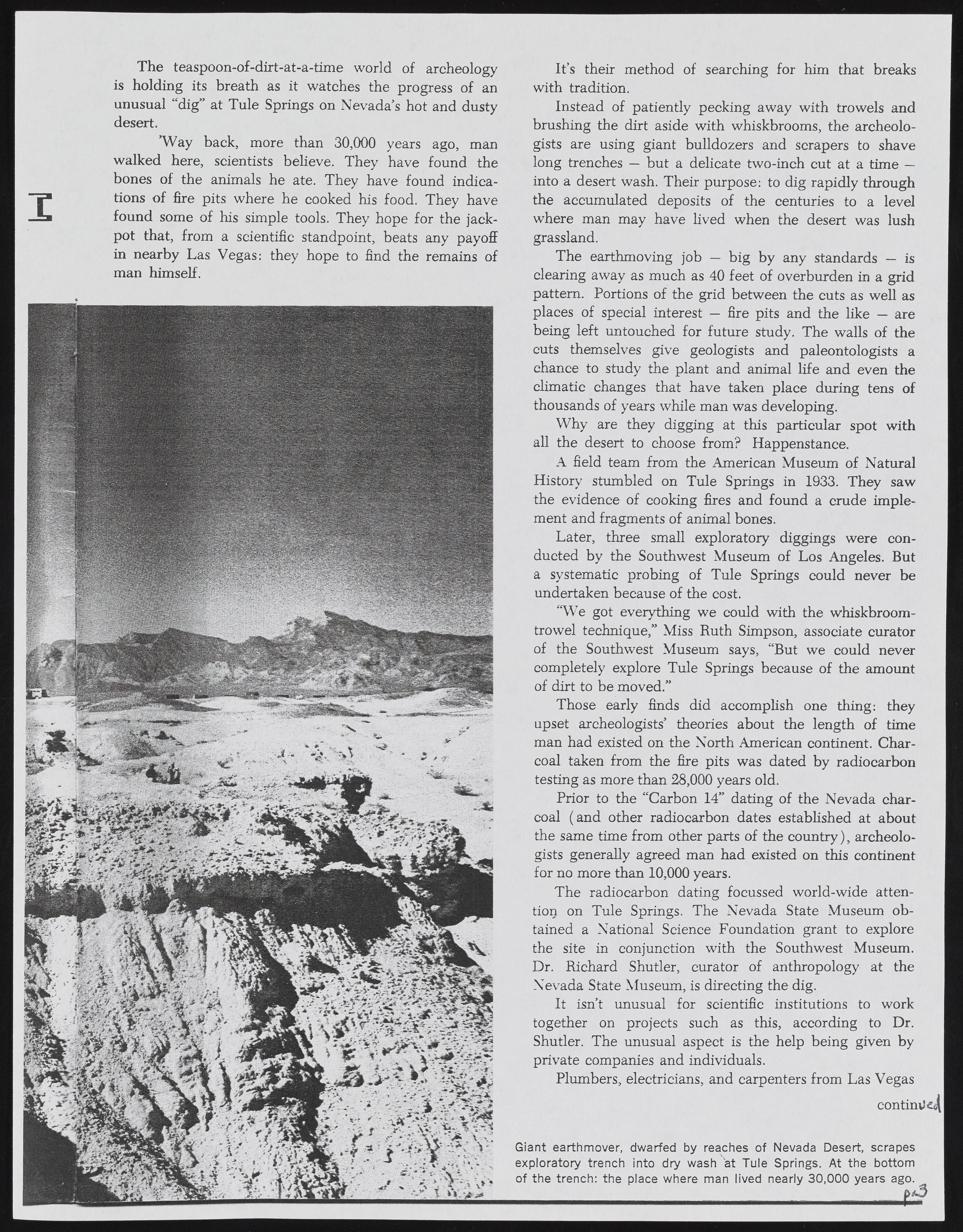

The teaspoon-of-dirt-at-a-time world of archeology is holding its breath as it watches the progress of an unusual “dig” at Tule Springs on Nevada's hot and dusty desert. 'Way back, more than 30,000 years ago, man walked here, scientists believe. They have found the bones of the animals he ate. They have found indications of fire pits where he cooked his food. They have found some of his simple tools. They hope for the jackpot that, from a scientific standpoint, beats any payoff in nearby Las Vegas: they hope to find the remains of man himself. 4 ? ? i n ,-rfe.si It's their method of searching for him that breaks with tradition. Instead of patiently pecking away with trowels and brushing the dirt aside with whiskbrooms, the archeologists are using giant bulldozers and scrapers to shave long trenches — but a delicate two-inch cut at a time — into a desert wash. Their purpose: to dig rapidly through the accumulated deposits of the centuries to a level where man may have lived when the desert was lush grassland. The earthmoving job — big by any standards — is clearing away as much as 40 feet of overburden in a grid pattern. Portions of the grid between the cuts as well as places of special interest — fire pits and the like — are being left untouched for future study. The walls of the cuts themselves give geologists and paleontologists a chance to study the plant and animal life and even the climatic changes that have taken place during tens of thousands of years while man was developing. Why are they digging at this particular spot with all the desert to choose from? Happenstance. A field team from the American Museum of Natural History stumbled on Tule Springs in 1933. They saw the evidence of cooking fires and found a crude implement and fragments of animal bones. Later, three small exploratory diggings were conducted by the Southwest Museum of Los Angeles. But a systematic probing of Tule Springs could never be undertaken because of the cost. “We got everything we could with the whiskbroom-trowel technique,” Miss Ruth Simpson, associate curator of the Southwest Museum says, “But we could never completely explore Tule Springs because of the amount of dirt to be moved.” Those early finds did accomplish one thing: they upset archeologists' theories about the length of time man had existed on the North American continent. Charcoal taken from the fire pits was dated by radiocarbon testing as more than 28,000 years old. Prior to the “Carbon 14” dating of the Nevada charcoal (and other radiocarbon dates established at about the same time from other parts of the country), archeologists generally agreed man had existed on this continent for no more than 10,000 years. The radiocarbon dating focussed world-wide attention on Tule Springs. The Nevada State Museum obtained a National Science Foundation grant to explore the site in conjunction with the Southwest Museum. Dr. Richard Shutler, curator of anthropology at the Nevada State Museum, is directing the dig. It isn't unusual for scientific institutions to work together on projects such as this, according to Dr. Shutler. The unusual aspect is the help being given by private companies and individuals. Plumbers, electricians, and carpenters from Las Vegas continUc4 Giant earthmover, dwarfed by reaches of Nevada Desert, scrapes exploratory trench into dry wash "at Tule Springs. At the bottom of the trench: the place where man lived nearly 30,000 years ago. t>*3