Copyright & Fair-use Agreement

UNLV Special Collections provides copies of materials to facilitate private study, scholarship, or research. Material not in the public domain may be used according to fair use of copyrighted materials as defined by copyright law. Please cite us.

Please note that UNLV may not own the copyright to these materials and cannot provide permission to publish or distribute materials when UNLV is not the copyright holder. The user is solely responsible for determining the copyright status of materials and obtaining permission to use material from the copyright holder and for determining whether any permissions relating to any other rights are necessary for the intended use, and for obtaining all required permissions beyond that allowed by fair use.

Read more about our reproduction and use policy.

I agree.Information

Digital ID

Permalink

Details

More Info

Rights

Digital Provenance

Publisher

Transcription

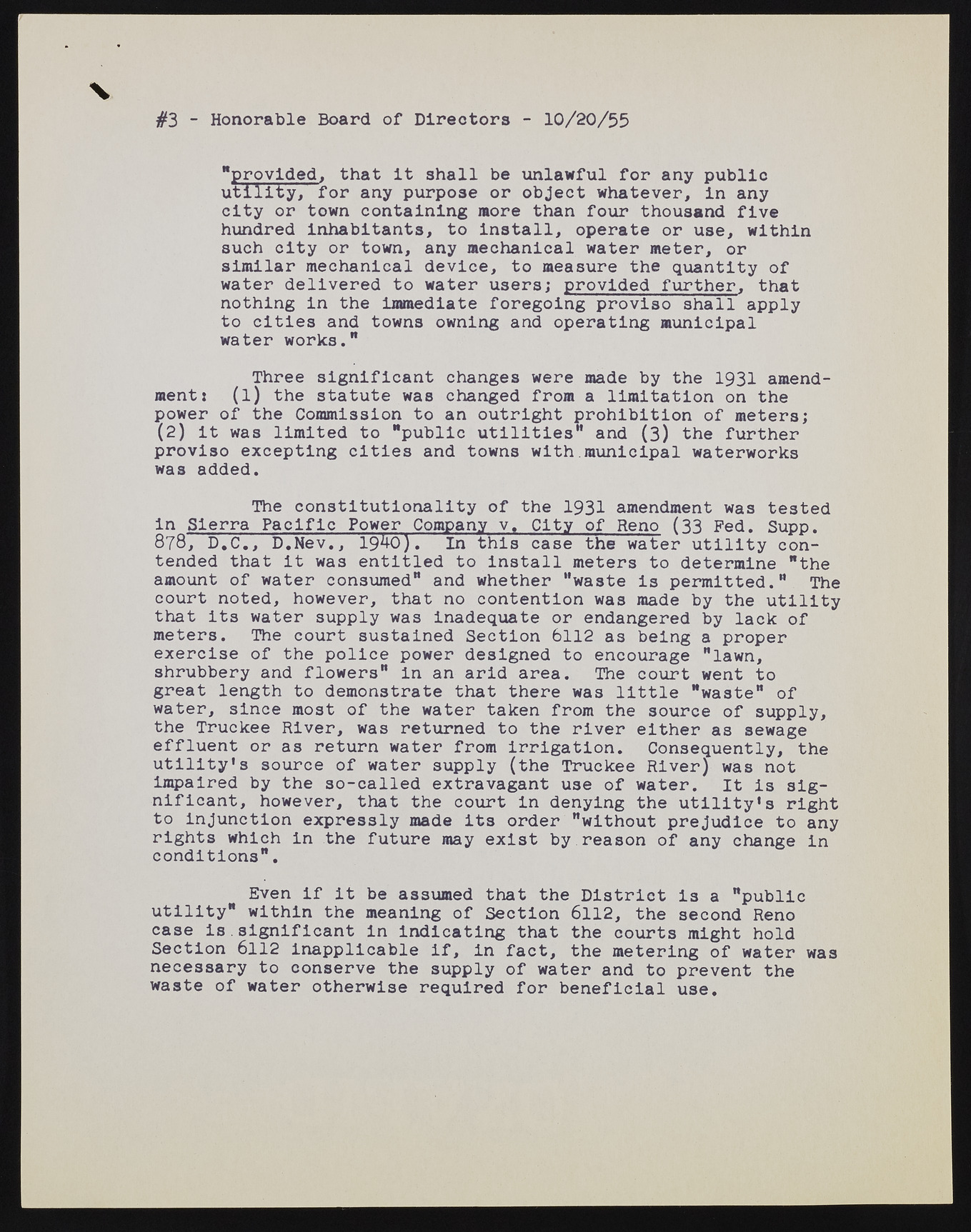

#3 - Honorable Board of Directors - 10/20/55 "provided, that it shall be unlawful for any public utility, for any purpose or object whatever, in any city or town containing more than four thousand five hundred inhabitants, to install, operate or use, within such city or town, any mechanical water meter, or similar mechanical device, to measure the quantity of water delivered to water users; provided further, that nothing in the immediate foregoing proviso shall apply to cities and towns owning and operating municipal water works." Three significant changes were made by the 1931 amendment: (l) the statute was changed from a limitation on the power of the Commission to an outright prohibition of meters; (2 ) it was limited to "public utilities" and (3 ) the further proviso excepting cities and towns with mimicipal waterworks was added. The constitutionality of the 1931 amendment was tested in Sierra Pacific Power Company v. City of Reno (33 Fed. Supp. 8 7 8 , D.C., D.Nev., 1940). In this case the water utility contended that it was entitled to install meters to determine "the amount of water consumed" and whether "waste is permitted." The court noted, however, that no contention was made by the utility that its water supply was inadequate or endangered by lack of meters. The court sustained Section 6112 as being a proper exercise of the police power designed to encourage "lawn, shrubbery and flowers" in an arid area. The court went to great length to demonstrate that there was little "waste" of water, since most of the water taken from the source of supply, the Truckee River, was returned to the river either as sewage effluent or as return water from irrigation. Consequently, the utility's source of water supply (the Truckee River) was not impaired by the so-called extravagant U3e of water. It is significant, however, that the court in denying the utility's right to injunction expressly made its order "without prejudice to any rights which in the future may exist by reason of any change in conditions". Even if it be assumed that the District i3 a "public utility" within the meaning of Section 6112, the second Reno case i s .significant in indicating that the courts might hold Section 6112 Inapplicable if, in fact, the metering of water was necessary to conserve the supply of water and to prevent the waste of water otherwise required for beneficial use.