Copyright & Fair-use Agreement

UNLV Special Collections provides copies of materials to facilitate private study, scholarship, or research. Material not in the public domain may be used according to fair use of copyrighted materials as defined by copyright law. Please cite us.

Please note that UNLV may not own the copyright to these materials and cannot provide permission to publish or distribute materials when UNLV is not the copyright holder. The user is solely responsible for determining the copyright status of materials and obtaining permission to use material from the copyright holder and for determining whether any permissions relating to any other rights are necessary for the intended use, and for obtaining all required permissions beyond that allowed by fair use.

Read more about our reproduction and use policy.

I agree.Information

Digital ID

Permalink

Details

More Info

Rights

Digital Provenance

Publisher

Transcription

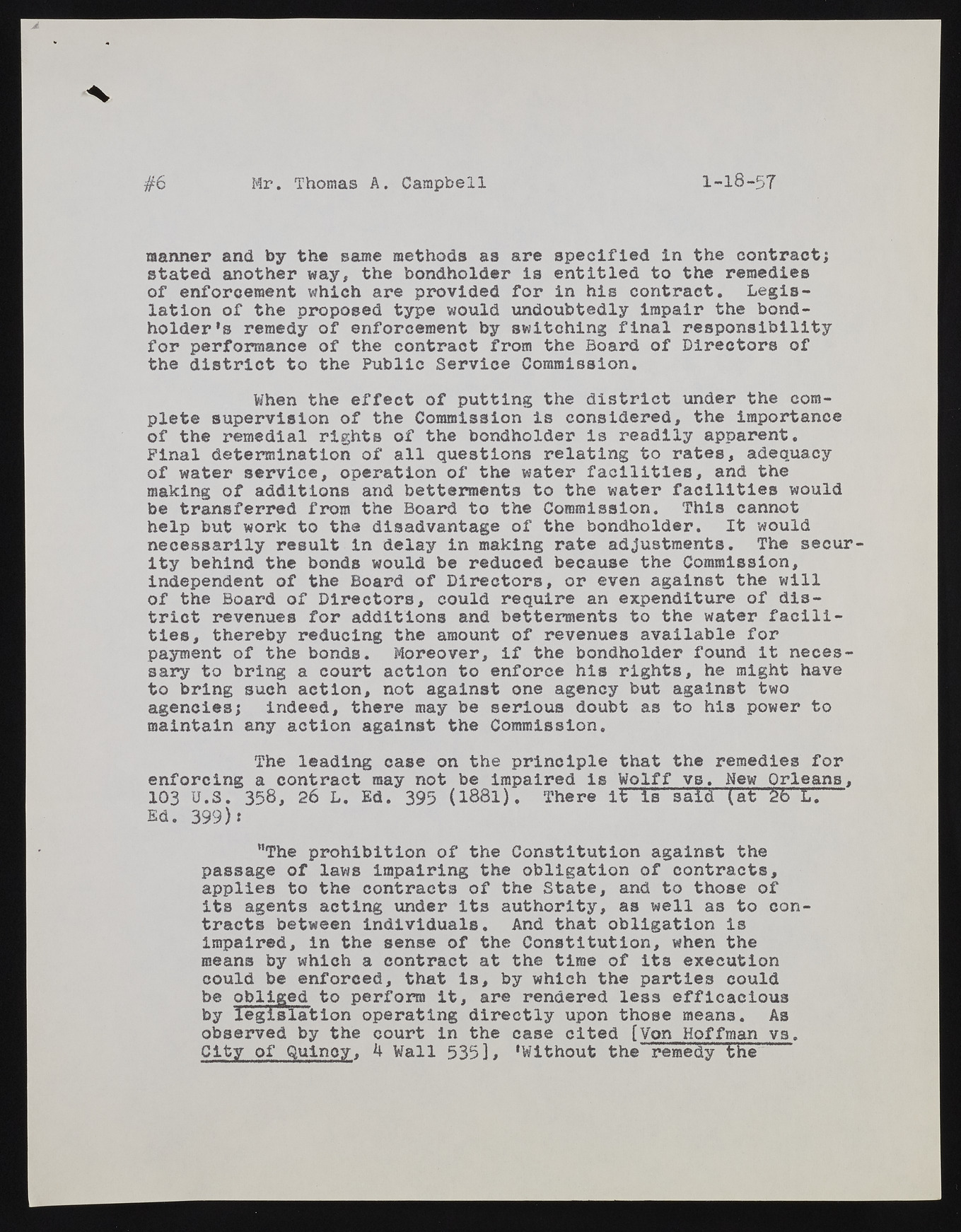

Mr. Thomas #6 A. Campbell 1-18-57 manner and by the same methods as are specified in the contract; stated another way, the bondholder is entitled to the remedies of enforcement which are provided for in his contract. Legislation of the proposed type would undoubtedly impair the bondholder's remedy of enforcement by switching final responsibility for performance of the contraot from the Board of Directors of the district to the Public Service Commission. When the effect of putting the district under the complete supervision of the Commission is considered, the importance of the remedial rights of the bondholder is readily apparent. Pinal determination of all questions relating to rates, adequacy of water service, operation of the water facilities, and the making of additions and betterments to the water facilities would be transferred from the Board to the Commission. This cannot help but work to the disadvantage of the bondholder. It would necessarily result in delay in making rate adjustments. The security behind the bonds would be reduced because the Commission, independent of the Board of Directors, or even against the will of the Board of Directors, could require an expenditure of district revenues for additions and betterments to the water facilities, thereby reducing the amount of revenues available for payment of the bonds. Moreover, if the bondholder found it necessary to bring a court action to enforce his rights, he might have to bring such action, not against one agency but against two agencies; indeed, there may be serious doubt as to his power to maintain any action against the Commission. The leading case on the principle that the remedies for enforcing a contract may not be impaired is Wolff vs. New Orleans, 103 U.S. 358, 26 L. Ed. 395 (l88l). There it is said (at £6 L. Ed. 399)* "The prohibition of the Constitution against the passage of laws impairing the obligation of contracts, applies to the contracts of the State, and to those of its agents acting under its authority, as well as to contracts between individuals. And that obligation is impaired, in the sense of the Constitution, when the means by which a contract at the time of its execution could be enforced, that is, by which the parties could be obliged to perform it, are rendered less efficacious by legislation operating directly upon those means. As observed by the court in the case cited [Von Hoffman v s . City of Quincy, 4 Wall 5353* 'Without the remedy the