Copyright & Fair-use Agreement

UNLV Special Collections provides copies of materials to facilitate private study, scholarship, or research. Material not in the public domain may be used according to fair use of copyrighted materials as defined by copyright law. Please cite us.

Please note that UNLV may not own the copyright to these materials and cannot provide permission to publish or distribute materials when UNLV is not the copyright holder. The user is solely responsible for determining the copyright status of materials and obtaining permission to use material from the copyright holder and for determining whether any permissions relating to any other rights are necessary for the intended use, and for obtaining all required permissions beyond that allowed by fair use.

Read more about our reproduction and use policy.

I agree.Information

Digital ID

Permalink

Details

More Info

Rights

Digital Provenance

Publisher

Transcription

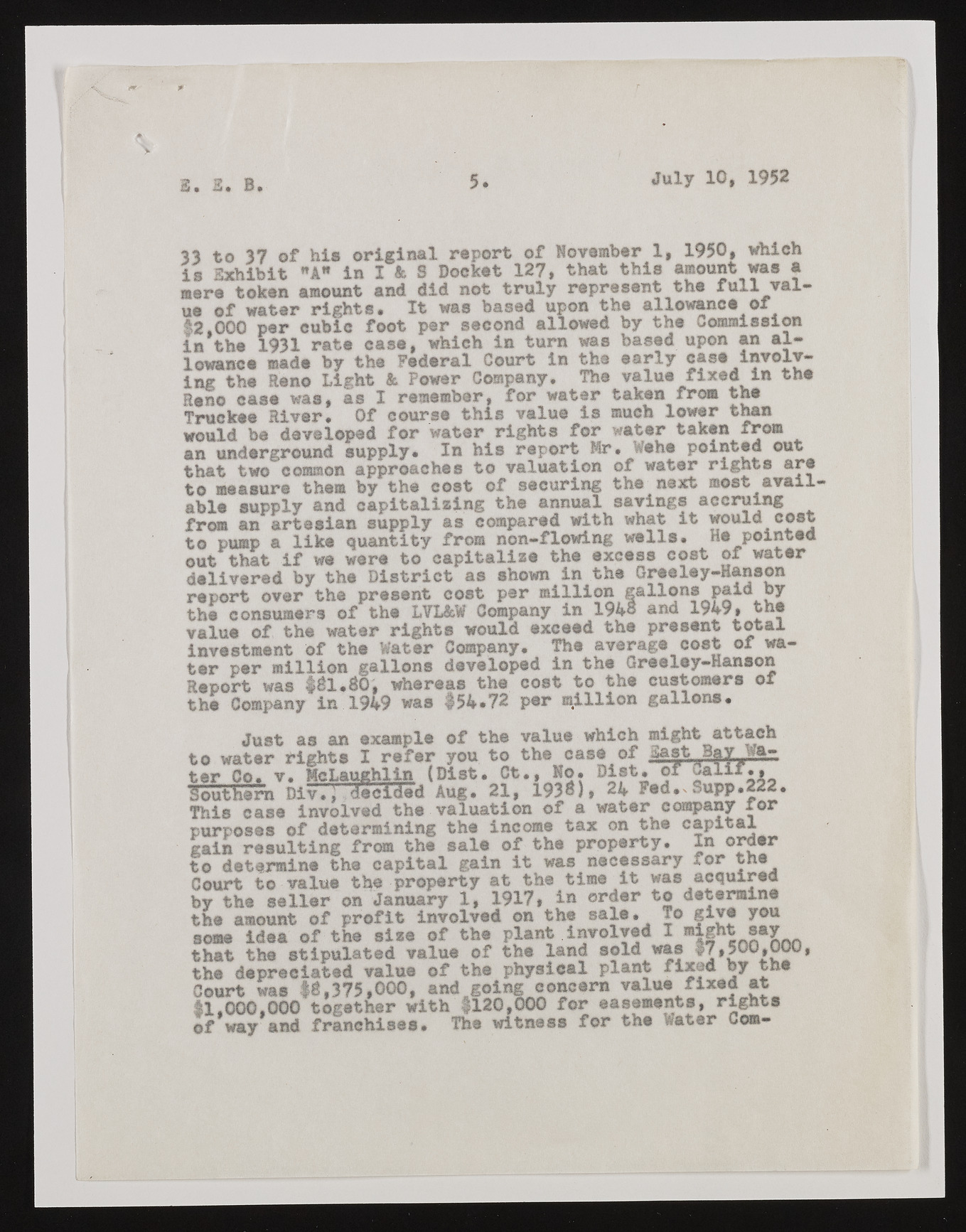

?&& « Jwi • B. 5. July 10, 1952 33 to 37 ©f his original report of November 1, 1 9 5 0 , which is Exhibit "A" in I k S Docket 127, that this amount was a mere token amount and did not truly represent the full value of water rights. It was based upon the allowance or #2,000 per cubic foot per second allowed by the Commission in the 1931 rate case, which in turn was based upon an allowance made by the Federal Court in the early case involving the Reno Light & Power Company. The value fixed in the Reno case was, as I remember, for water takenfrom the Truckee River. Of course this value is much lower than would be developed for water rights for water taken from an underground supply. In his report M r • Wehe pointed out that two common approaches to valuation of water rights are to measure them by the cost of securing the next most available supply and capitalising the annual savings accruing from an artesian supply as compared with what it would cost to pump a like quantity from non-flowing wells. He pointec out that if we were to capitalize the excess cost of water delivered by the District as shown in the Greeley-Hanaon report over the present cost per million gallons paid by the consumers of the LVX&W Company in 194© and 1949, the value of the water rights would exceed the present total investment of the Water Company. The average cost of water per million gallons developed in the Greeley-Hanson Report was 461*60, whereas the cost to the customers or the Company in 1949 was 454.72 per pillion gallons. Just as an example of the value which might attach to water rights I refer you to the case of t e s t Bay ter Co. v. McLaughlin {Dist. Ct., No. Dist. of Calif*, Southern Div., decided Aug. 21, 1936)» 24 Fed.^Supp.222. This case involved the valuation of a water company for purposes of determining the income tax on the capital gain resulting from the sale of the property. In order to determine the capital gain it was necessary for the Court to value the property at the time it was acquire® by the seller on January 1, 1917, in order to determine the amount of profit involved on the sale. To give you some idea of the size of the plant involved X JKJght say that the stipulated value of the land sold was 17,500,000, the depreciated value of the physical plant fix^d by the Court was 16,375,000, and going concern value fixed at 1 1 .0 0 0 ,0 0 0 together with #1 2 0 ,0 0 0 for easements, rights of way and franchises. The witness for the Water Com—