Collection Paragraphs

10,000 years ago, perhaps even more, Native Americans began migrating to the area that was to become Lake Mead. The documented history of the area began in 1827 when Jebediah Smith found various artifacts while exploring Southern Nevada. Pueblo Grande de Nevada, a complex of villages, was first seen by whites in 1867. There was little interest in the area until 1924 when John and Fay Perkins, citizens of Overton, Nevada, stumbled across the ruins. The "Lost City" captured the imagination of Nevada and soon became a tourist spot.

Encouraged by the Nevada state government, archaeologist M.R. Harrington, of the Heye Foundation of New York, headed a study of the Pueblo Grande de Nevada. Prior to Harrington’s expedition, it was believed that the Pueblo people had not migrated west of the Colorado River into Nevada. However, the existence of the ruins proved that the Pueblo had been a major presence in southern Nevada.

In studying the ruins, Harrington and his team learned that the Pueblo had only been one group in a string of Native American inhabitants living throughout the lower Moapa Valley, the location of Pueblo Grande de Nevada. Archaeological remains indicated that the first people to live in the area had been the Basketmakers, so-named for their intricate and prolific use of basketry. Eventually the Pueblo people moved into the area. The evidence suggests that the Pueblo and Basketmakers lived side by side, often combining their ways of life. Whether by peaceful means or through war, the cause for this melding of cultures is unknown.

Before the Pueblo, the Basketmakers had constructed their homes underground in the pit-house form. But the Pueblo introduced adobe above ground structures. More than just simple one-room houses, the structures of the Lost City were often very elaborate sometimes consisting of 20 rooms or more with one structure reaching over 100. An interesting mix of living styles existed in the Lost City with surface houses being used in conjunction with the earlier pit houses.

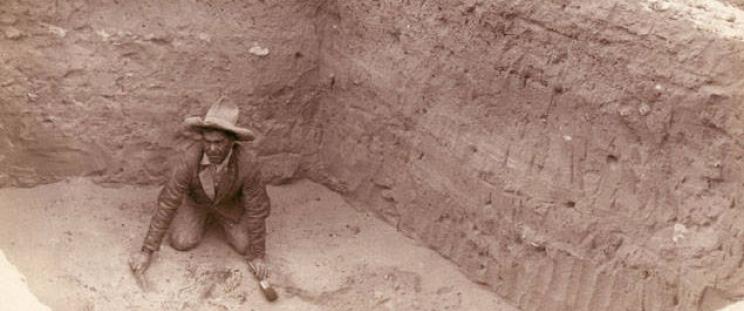

Even though the last inhabitants of the Lost City had left hundreds of years earlier (the Paiute), the city was a remarkable find for archaeologists and historians. Unearthing walls, tools, weapons, food, and even skeletal remains provided archaeologists the basis for studying and understanding an important part of Native American history. However as the Hoover Dam was nearing completion it became apparent that the reservoir that would be formed behind the dam, Lake Mead, would eventually cover the Lost City. The National Park Service, working with the state of Nevada, rushed to recover as much information as possible from the doomed sites. Archaelogists literally worked up until the last minute, recording information as water began to seep into the site.

Not all sites were drowned by the Lake, but the most representative, Pueblo Grande de Nevada (Lost City) was. Luckily, hundreds of sites remained above water and various artifacts were saved from the Lost City to be housed in the Lost City Museum of Archaeology in Overton, Nevada. But for every discovery saved, myriad others were lost. All future study of the area would be limited to the hastily assembled collections and notes of the pre-Lake Mead archaeologists. By the 1950s it was already obvious to historians, archaeologists, and anthropologists that the surviving artifacts of Lost City raised more questions than answers. Answers that would remain lost at the bottom of Lake Mead.