Copyright & Fair-use Agreement

UNLV Special Collections provides copies of materials to facilitate private study, scholarship, or research. Material not in the public domain may be used according to fair use of copyrighted materials as defined by copyright law. Please cite us.

Please note that UNLV may not own the copyright to these materials and cannot provide permission to publish or distribute materials when UNLV is not the copyright holder. The user is solely responsible for determining the copyright status of materials and obtaining permission to use material from the copyright holder and for determining whether any permissions relating to any other rights are necessary for the intended use, and for obtaining all required permissions beyond that allowed by fair use.

Read more about our reproduction and use policy.

I agree.Information

Digital ID

Permalink

Details

More Info

Rights

Digital Provenance

Publisher

Transcription

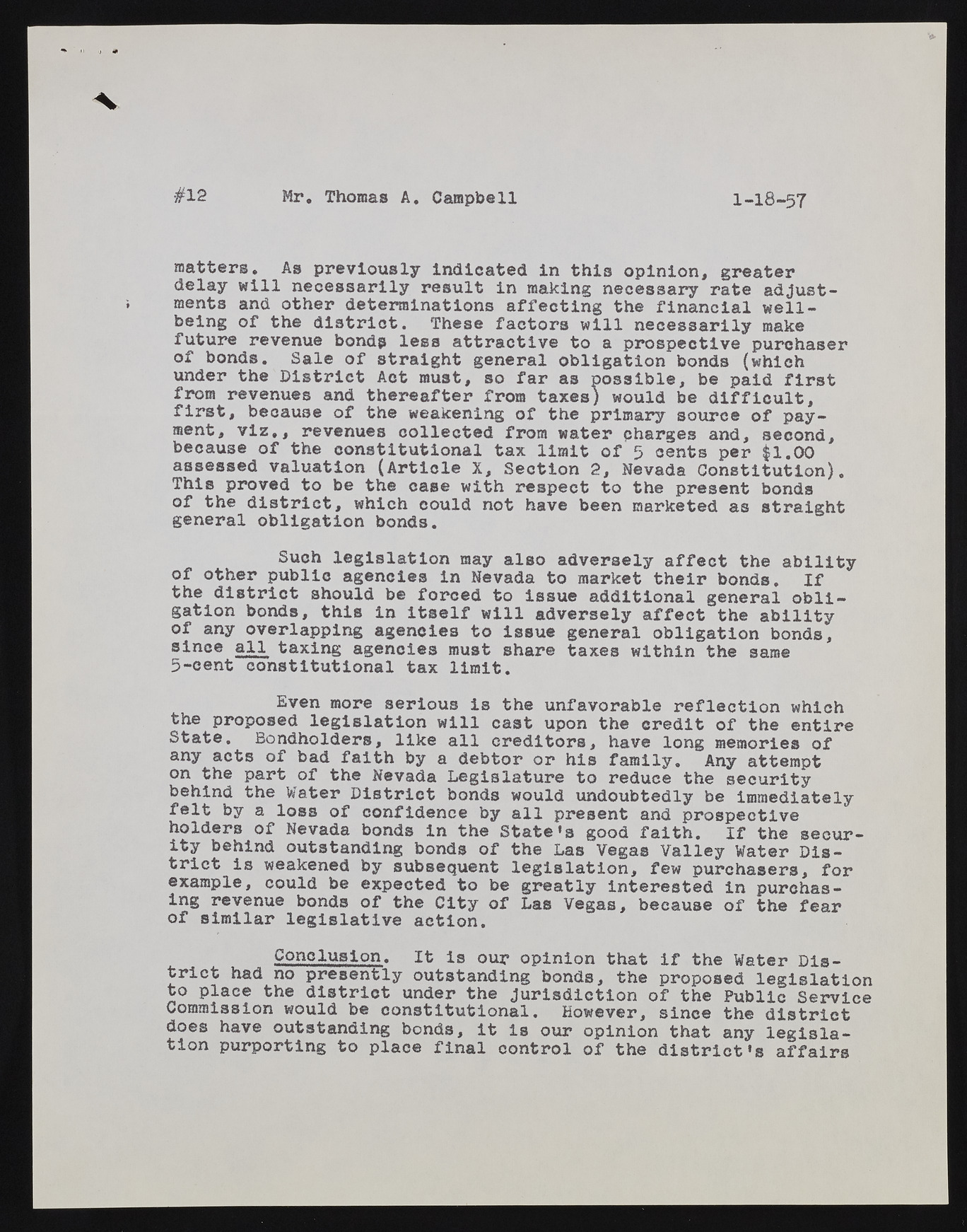

#12 Mr. Thomas A. Campbell 1 -1 8 - 5 7 matters. As previously indicated in this opinion, greater delay will necessarily result in making necessary rate adjustments and other determinations affecting the financial wellbeing of the district. These factors will necessarily make future revenue bonds less attractive to a prospective purchaser of bonds. Sale of straight general obligation bonds (which under the District Act must, so far as possible, be paid first from revenues and thereafter from taxes) would be difficult, first, because of the weakening of the primary source of payment, viz., revenues collected from water pharges and, second, because of the constitutional tax limit of 5 cents per $1.00 assessed valuation (Article X, Section 2, Nevada Constitution). This proved to be the case with respect to the present bonds of the district, which could not have been marketed as straight general obligation bonds. Such legislation may also adversely affect the ability of other public agencies in Nevada to market their bonds. If the district should be forced to issue additional general obligation bonds, this in itself will adversely affect the ability of any overlapping agencies to issue general obligation bonds, since all taxing agencies must share taxes within the same 5-cent constitutional tax limit. Even more serious is the unfavorable reflection which the proposed legislation will cast upon the credit of the entire State. Bondholders, like all creditors, have long memories of any acts of bad faith by a debtor or his family. Any attempt on the part of the Nevada Legislature to reduce the security behind the Water District bonds would undoubtedly be immediately felt by a loss of confidence by all present and prospective holders of Nevada bonds in the State*s good faith. If the security behind outstanding bonds of the Las Vegas Valley Water District is weakened by subsequent legislation, few purchasers, for example, could be expected to be greatly interested in purchasing revenue bonds of the City of Las Vegas, because of the fear of similar legislative action. Conclusion. It is our opinion that if the Water District had no presently outstanding bonds, the proposed legislation to place the district under the Jurisdiction of the Public Service Commission would be constitutional. However, since the district does have outstanding bonds, it is our opinion that any legislation purporting to place final control of the district’s affairs